In recent weeks with the slower pace at the farm during colder weather we’ve turned our attention to a series of special events featuring our Palouse Heritage grain flours. Having participated in every Cascadia Grains Conference that the Jefferson County Extension Service has held in Olympia for the past five years, we were honored again this past January to present at the “Taste the Grain” dinner held at historic Schmidt House. The mansion was built a century ago in Colonial Revival style for the founders of Olympia Brewing and was an ideal setting for us to sample the array of breads and brews provided by Rob Salvino at Seattle’s Damsel & Hopper Bakeshop, South Sound Community College Culinary Science chefs Kelly McLaughlin and Isaac Gillett, and Copperworks Distillery.

Puget Sound Community College “Palouse Heritage” Chefs

Since my task was simply to tell stories about the various heritage grains and heartily sample the many courses, I far and away had the most pleasant role for what was a wonderful evening. County extension personnel and conference organizers Lara Lewis and Aba Kiser skillfully handled the many logistics since we were spread across the state, and thanks to Rob, Kelly, and Isaac’s special talents the capacity crowd had an incredibly delicious menu. (Among the many guests was our special Palouse Colony Farm artist friend from Washington, D. C., Katherine Nelson. I will follow this post with another about her life and work.)

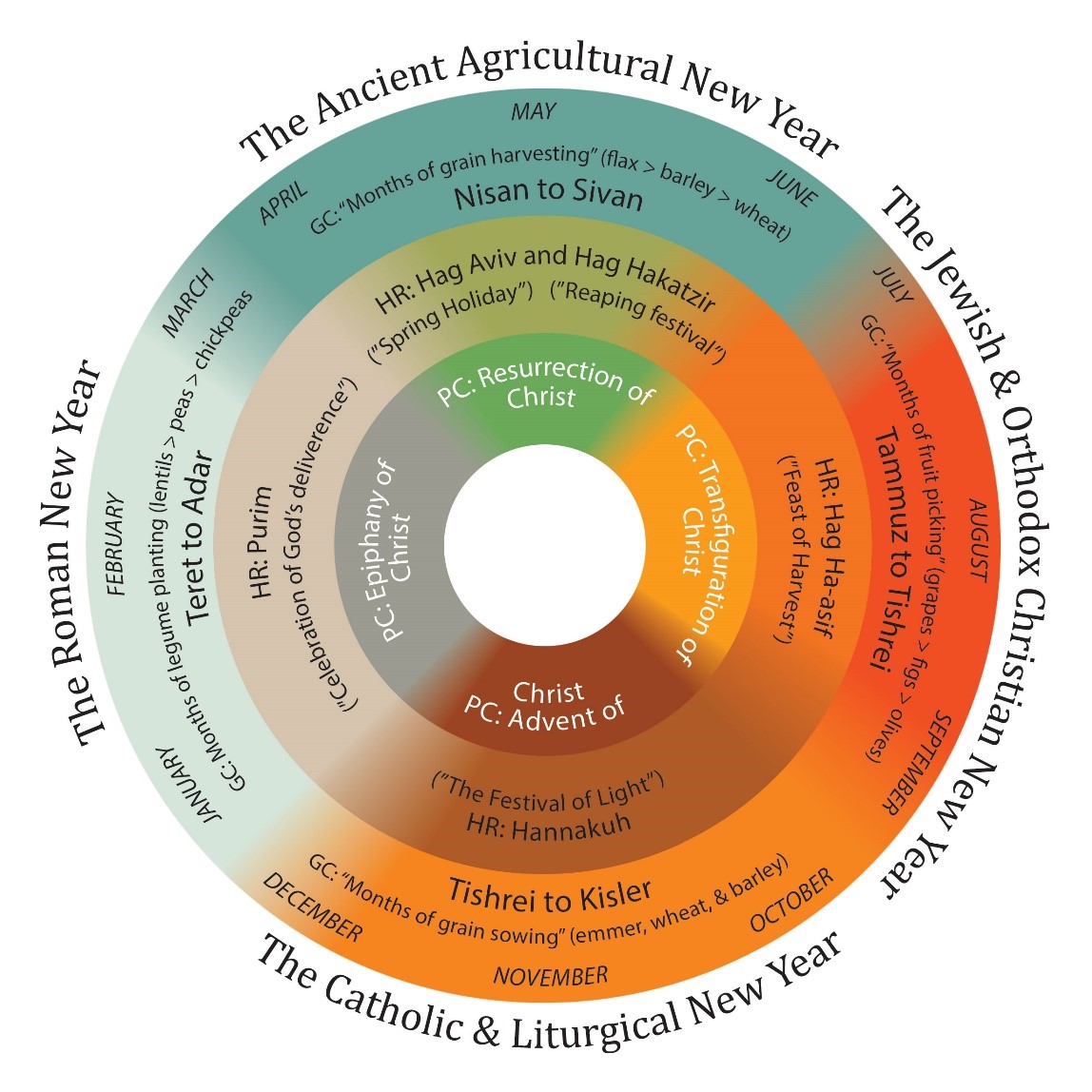

Below is the dinner menu we formulated for the evening, and for the first time we included a series of pairings featuring craft brews and distilled products. Of course we can’t guarantee that you’d find these offered on the bill of fare at famed The Spar in downtown Olympia during the periods specified, but there are historical reasons for these combinations.

1. 1820s-1850s: Fur Trade and Frontier Era

Smoked beef brisket with blue cheese and lavender honey on rosemary crackers made with Palouse Heritage Sonoran Gold wheat flour / Paired with Top Rung’s My Dog Scout Stout

2. Pork Belly Crostini: Candied pork belly with leek strata, roasted tomato, and mascarpone on charred crostini made with Palouse Heritage Sonoran Gold wheat flour / Paired with Copperworks Whiskey

3. 1860s-1870s: Northwest Pioneering and Townbuilding

Salted maple, apple, and mascarpone galette made with Palouse Heritage Empire Orange and Crimson Turkey wheat flours / Paired with Fremont Brewing’s Universale Pale Ale

4. Chili Lime Prawns: Colossal prawns, arugula, chili, lime, chive, basalmic caviar and barley tuile using Palouse Heritage Purple Egyptian barley flour

5. 1890s-1910s: Waves of Immigrants and Golden Grains

Focaccia di Recco and crispy pancetta made with Palouse Heritage Crimson Turkey wheat flour, rosemary, Kalamata olives, sundried tomatoes, and 4 cheeses / Paired with Ghost Fish IPA

6. Gin and Tonic Tart: Lemon egg tart using Palouse Heritage Turkey Red wheat flour with gin and tonic simple syrup using Sandstone Stonecarver Gin

Thanks again Rob, Lara, Aba, Kelly, Isaac, and Olympia historian Don Prosper for such a marvelous event!