Ancient Grains & Harvests (Part 4)

Sacred Ways and Field Labors

Recent studies of earthenware ostracha from the fortress of Arad near the Dead Sea discovered in the 1960s date to approximately 600 BC during the reign of King Jehoiakim (II Kings 24) and reveal the prevalence of grain, flour, and bread deliveries along with wine and oil to the remotest desert reaches of the Kingdom of Judah. Written in ancient Hebrew using the Aramaic alphabet, these pottery shards served as vouchers presented to the commander to issue supplies from the fort’s storehouses. The Prophet Ezekiel served as a priest among the Jewish exiles to Babylon during this period and makes specific reference to wheat, emmer, barley, lentils, and other crops (e.g., 4:16, 5:16) in the context of early references to the “staff of bread,” which was life’s great sustainer in the ancient world. Basic units of common linear measurement owe their origin to grain; as the length of two barley kernels represented the Old Testament “finger-breadth” of three-tenths of an inch, twenty-four were an eight-inch “span,” and forty-eight a “cubit” of sixteen inches.

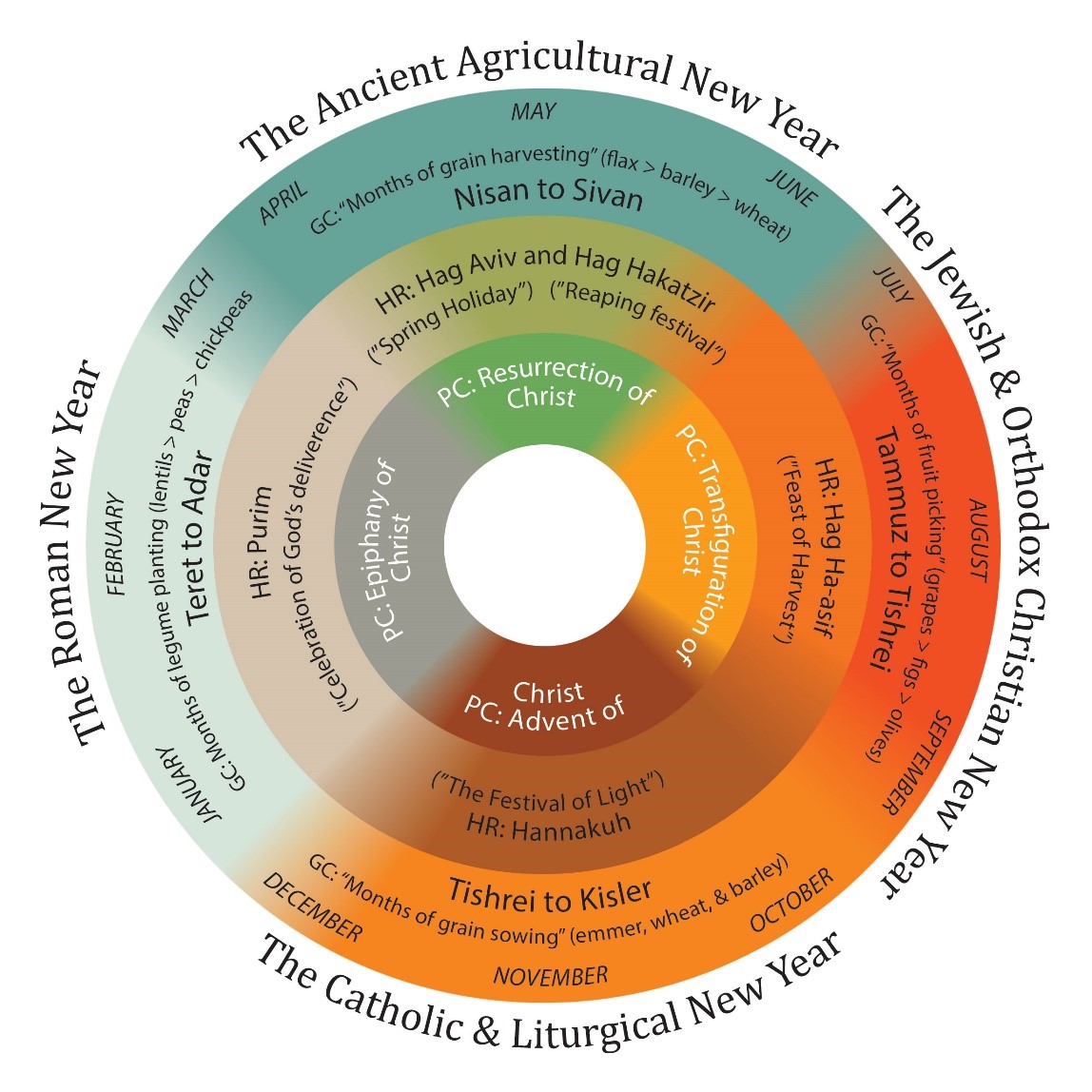

Anglican scholar-priest Rev. Philip Carrington (1892-1975), Metropolitan of Canada, undertook extensive study on the relationship between the first century arrangement of Mark’s gospel into a lectionary series that relates the ancient Jewish ritual year and Galilean lunar agricultural cycle to key events in the life of Christ. Carrington proposes that this sequence of Christ’s public Galilean ministry—the culmination of his life on earth, involving the Feeding of the Five Thousand, Seed-time and Harvest Parables, and other agrarian-related discourses and happenings significantly shaped the “Primitive Christian Calendar” that in turn gave rise to the Early Church’s liturgical calendar.

In commentary on Mark’s culminating New Testament message of resurrection, Carrington writes of the “mystical and symbolical way of thought which was natural to men at that time, and found expression in art and poetry and ritual and drama and religion. In the springtime life returns from the underworld in leaves and grasses and flowers; when the harvest comes, it is cut down in the shape of fruit and grain; it dies, but it will come again. Such is the destiny of man. Old Nature, who is the mother of mankind, reflects on her many-coloured drama on the destiny of her divine son. Such is the truth that underlies the old way of thought.” Carrington concludes that the culture of the disciples was connected to the old festivals, and that their memories “would tend to arrange themselves in the order of the Calendar Year; and seeing that the Lord chose to express himself in these surroundings in the terms of the old agricultural and festal mysticism. And, if so, we may ourselves enter into the tradition and gain some understanding of it, not merely by literary and critical study along these lines, but by passing through the devotional course of the Christian Year, as it has come down to us in the Church.”

Agricultural laws that guided ancient Hebrew spiritual and civil life are described in the third century AD Mishnaic collection of oral traditions and include blessings for foods and landowner obligations to provide produce for the Levites of the temple, priests, and the poor. In a medieval commentary on Jewish piety, Hokhmat ha-Nefesh, Rabbi Elezar Ben Judah of Worms (c. 1126-1238) celebrated the Hebrew agrarian ideal: “God created the world so all should live in pleasantness, that all shall be equal, that one should not lord over the other, and that all may cultivate the land.” Faith-based perspectives on creation stewardship were expressed by 16th century French theologian John Calvin: “The custody of the garden was given in charge to Adam, to show that we possess the things which God has committed to our hands, on the condition that… we should take care of what remains. Let him who possesses a field, so partake of its yearly yield, that he may not suffer the ground to be injured by his negligence, but let him endeavor to hand it down to posterity as he received it, or even better cultivated.”

Correlation of Ancient Ritual and Agricultural Calendars with Crop Sequences, GC: Gezer Calendar, HR: Hebrew Ritual, PC: Primitive Christian

American Country Life Movement leader Liberty Hyde Bailey elaborated on this ethic in his 1915 classic, The Holy Earth: “If God created the earth, so is the earth hallowed; and if it is hallowed, so must we deal with it devotedly and with care that we do not despoil it….. We are to consider it religiously: ‘Put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.’ …I do not mean all this, for our modern world, in any vague or abstract way. If the earth is holy, then the things that grow out of the earth are also holy.” A landowner’s obligation as steward of the earth’s bounty also extended to the less fortunate. One of the earliest biblical references to gleaning (Leviticus 23:22) appears in instructions on the principal Hebrew feasts and ritual thank offering (Todah) of the first grain harvest sheaves to be waved and presented to the priests: “And when you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap your field right up to its edge, nor shall you gather the gleanings after your harvest. You shall leave them for the poor and for the sojourner.” From these and related Mosaic references (e.g. Deuteronomy 24:19), Jewish laws developed that were fundamentally different than prevailing customs in Egypt, Greece, Rome, and elsewhere in the ancient Mediterranean world where such rights were not extended to the poor. These customs guided the process of gleaning, a practice that still continues in some rural areas of Syria, Lebanon, and elsewhere in the Middle East. (English “glean” is from Anglo-French glener, “to collect, gather,” a word derived from Latin glennāre which is probably of Celtic origin.)

Old Testament prohibitions of representational art influenced the rich expression of literary imagery in Hebrew literature. While Greek aesthetics were occupied with spatial unity and static forms of sculpture, the Hebrew mind understood God as the ideal so such literature often incorporates mixed metaphors for more tactile expressions of meaning, often in the context of agrarian experience that marked the seasons with times and festivals for planting, harvest, threshing, and winnowing. One of the finest examples is the c. 10th century BC story of Ruth which relates her rescue by a kinsman-redeemer, Boaz, after her travels to the land of her mother-in-law, Naomi, in the aftermath of famine in Israel. The author’s imagery is as much about Hebrew culture as theological doctrine, and forthrightly describes the women’s sojourn, fidelity, and redemption amidst opening scenes that follow the workers’ harvest: “And Ruth the Moabite said to Naomi, ‘Let me go to the field and glean among the ears of grain after him in whose sight I shall find favor.” And she said to her, ‘Go, my daughter.’ So she set out and went and gleaned in the field after the reapers, and she happened to come to the part of field belonging to Boaz...” (Ruth 2:2-3).

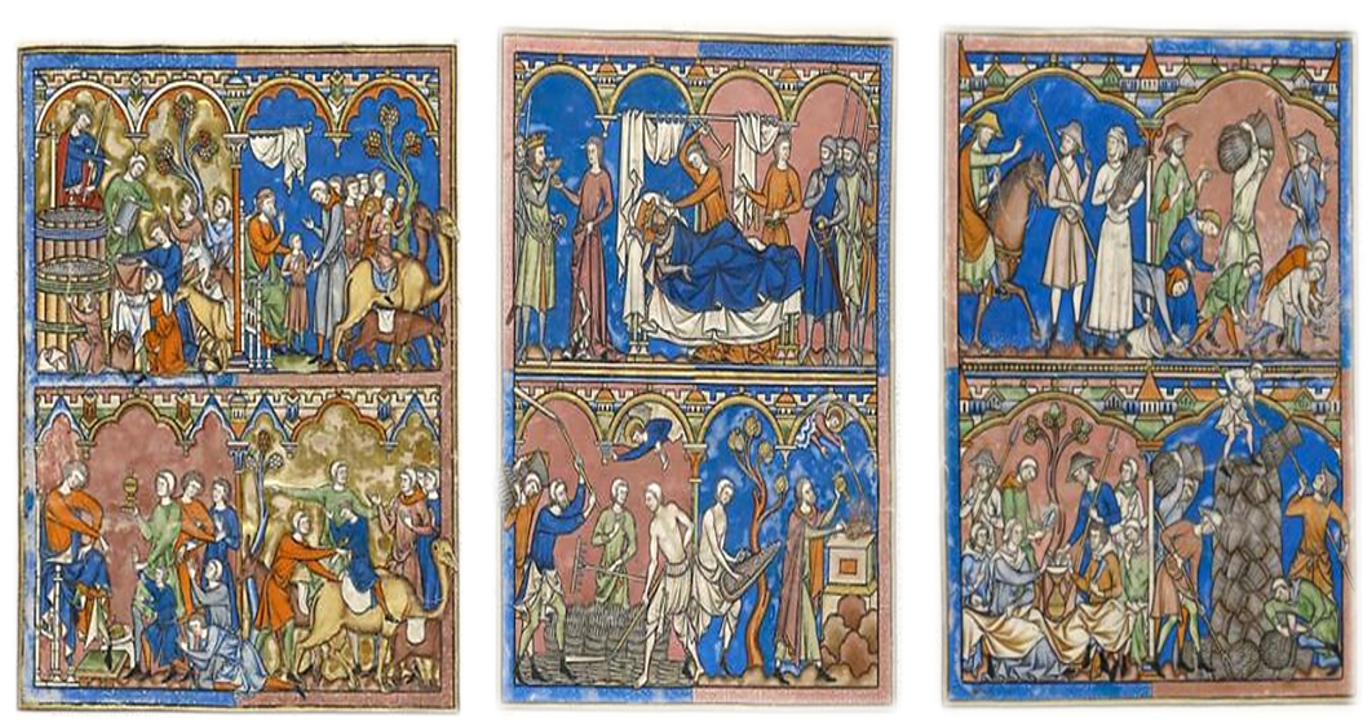

Crusader (Maciejowski) Bible (c. 1240s); illuminated vellum, 15 ⅓ x 11 ⅘ inches; Left: Folio 6—An Ironic Turn of Events (Genesis 42), with Joseph supplying his brothers with grain (top right); Center: Folio 12—Gideon, Most Valiant of Men (Judges 6), with Gideon threshing wheat (bottom left); Right: Folio 17—Ruth Meets Boaz (Ruth 2), with reapers cutting grain followed by Ruth gleaning (top right); The Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, New York

Early Modern Woodcuts of Ruth and Boaz; Left to right: Gerard de Jode (1585); Mattias Scheits and François Halma (1710); Palouse Regional Studies Collection

Beneath the familiar tale rests a complex doubling motif in theme and between poor and rich, women and men, and threshing and waiting. The interplay is evident throughout the narrative and poetic couplets to amplify the contrast between destitution and bounty. The famine experienced by Naomi and her family was in Bethlehem—literally “House of Bread,” but her sons perish in Moab, the land of bounty. Divine deliverance is timeless and confounds human reason. Cereal provisions were an important indication of blessing. Wheat (hittim) and barley (s’orim) breads likely made up almost half of the Hebrew diet and was served in some form at virtually every meal that also may have featured parched or boiled grains in mixtures with fruits and in gruels. The ubiquity of wholesome grains in Ruth throughout the Bible speaks of their nutritional, intellectual, and spiritual significance in Hebrew culture. Harvest time happenings, familiar to most any inhabitant of Moab or Judah, provide the context for lessons on how God provides deliverance to the ordinary faithful in a world of injustice and chaos.

The short four-chapter book’s timeless theme of redemption from deprivation and distress to promise of new life has inspired generations of believers, authors, and artists with styles ranging from the Baroque formalism of Barent Pietersz Fabritius to Marc Chagall’s richly flowing Surrealism. An early 14th century Jewish prayer book from Germany illustrates Ruth’s story in lush gold, red, and blue tones. Although the scene depicts the grain rakes, threshing flails, and clothing of medieval Europe, it faithfully depicts Boaz’s care and the blessing of the harvest. Thomas Rooke’s idealist 19th century interpretation shows the couple and Naomi as they might have appeared in the garb of ancient times, but other renderings like Jean-François Millet’s evocative Harvesters Resting (1850) are cast in settings of the artists’ lifetimes to suggest the ancient story’s abiding relevance.