In Memory of Micala Hicks Siler (1978-2020)

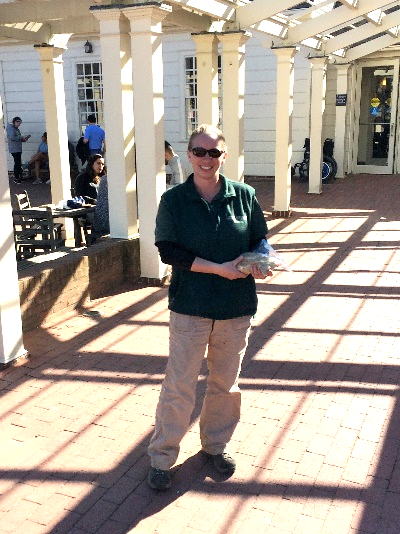

Devoted Wife and Mother, Humanitarian, West Point Graduate and Soldier

“Van Gogh & European Landscapes” Exhibit Entry (March-September 2022)

Dayton Art Institute; Dayton, Ohio

This day dawned for us in Dayton, Ohio, while on a cross-country road trip to the East Coast and where we enjoyed the fellowship of longtime friends from the Siler and Hicks families who visited Palouse Colony Farm in 2018. Micala served as founding director of A Family for Every Orphan which has found caring homes for children in need inside their countries of origin in eastern Europe, Africa, and Asia. Since we are exploring sites of interest along the way during our trip, a chance viewing of the Dayton Art Institute’s website this week reported on a special exhibit of masterful paintings by prominent 19th century European landscapists. It included works from Vincent van Gogh’s acclaimed Wheatfield series—the great artist’s last creations. Although I had read about his remarkable life, I had never seen one of van Gogh’s landscapes in person so took advantage of our stay to do so.

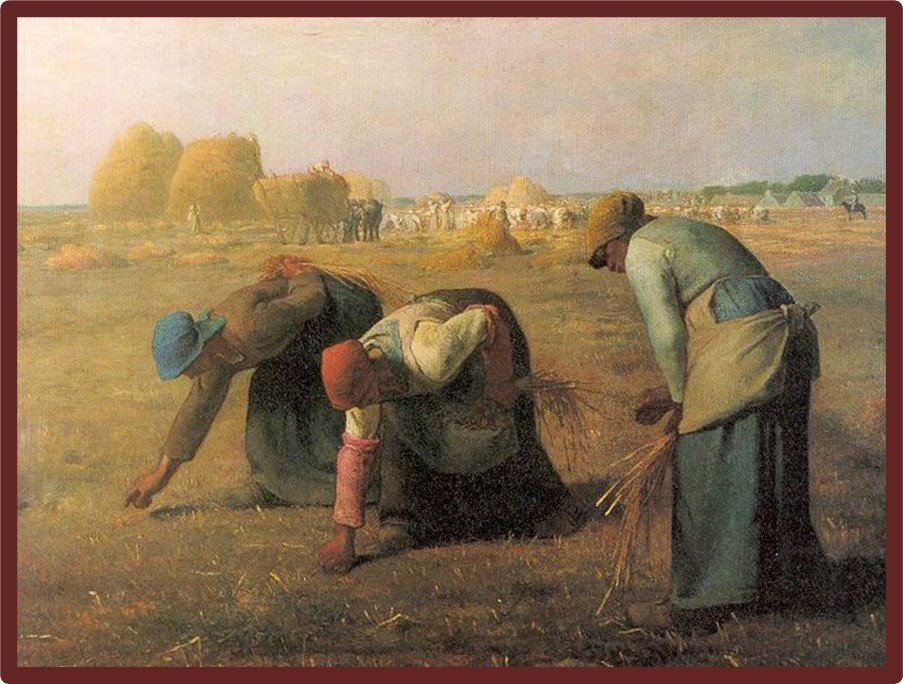

Although Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) never met famed “painter of peasants” Jean Millet (1814-1875), he was familiar with the artist since working enthusiastically as a young man in his uncles’ print-dealer firm at The Hague. In 1875 van Gogh attended an 1875 Paris exhibition of Millet’s larger works which greatly impressed him. Van Gogh also studied religious prints by socially conscious Gustave Doré (1832-1883) and agrarian works by Jules Breton (1827-1906) like The Blessing of the Wheat and The Gleaner. He came to speak of Millet and Breton in the same breath as kindred spirits whose art he called “the voice of the wheat,” and found the form of a sheaf an “enchanting symbol” of the infinite.

A profound intellectual and prolific correspondent despite mental and physical ailments, van Gogh read Zola, Dickens, and the classics, studied Delacroix and Rembrandt, and acquired engravings by Millet and other artists. Soon after deciding to become an artist in 1880, he read Alfred Sensier’s influential biography, Le Vie et L’Oeuvre de Jean-François Millet. The young artist found revelatory meaning in its portrayal of Millet akin to his own search for meaning through a consilience of faith and art in the natural world. In van Gogh’s Noon: Rest from Work, after Millet (1890), poet Allen Braden viewed the revolutionary artist’s depiction of Ruth and Boaz “serene in their exhaustion” and a kind of noble statement “…on the balance / between art and whatever is perfectly ordinary.”

Jean-François Millet, The Gleaners (1857)

Oil on canvas, 33 x 44 inches

Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Wikimedia Commons

Through his older contemporaries’ romanticized depictions of peasant endeavor, van Gogh saw the primal values of stoic faith, dignified simplicity, and honorable toil. His supremely passionate landscapes and portraits are devoid of complicated narratives. Rather, van Gogh chose commoners and the commonplace to show forth the everyday glories of faces, fields, and flowers in ways never before expressed. These views he enveloped in exaggerated colors from light lemon to orange, Prussian blue, Veronese green, and other seasonal shades of that anticipated Modernism. Few Impressionists apart from Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), however, had painted peasants, and his “Independent” version represented serious regard for the sufferings of the poor which he understood to foreshadow the emerging era’s granulation of the individual.

Pissarro found the self-reliant ways of rural cooperatives to offer the most practical means of cultivating humanity. This relationship is seen in the laboring souls depicted with hopeful, well-tended terrains of blue greens, russets, and pale yellows of in his masterpieces The Harvest (1882) and The Gleaners (1889). Summer, from the Four Seasons series (1872-1873) painted for the dining room of his patron Achille Arosa, shows three approaching peasants in the center of the canvas who are dwarfed by a prodigious field of dappled bundles and standing grain beneath an immense blue sky. In contrast to traditional allegorical themes, Pissarro’s painting is without religious or other cultural symbolism in testimony to exquisite vernacular beauty.

Pissarro met van Gogh in Paris in 1887 and encouraged him to brighten his somber palette. Amidst the Provençal mistral winds in June 1888, van Gogh passionately painted a group of at least nine “Harvest” paintings which provided opportunity to experiment with technique and color. He worked quickly in the vicinity of Arles, often reveling in the heat of day, “just like the harvester, …intent only on the reaping,” and blended striking hues of gold, copper, and bronze with yellow, red, and brown. In a letter to his brother and abiding benefactor Theo the following June, van Gogh expressed special interest in the patchwork of green and yellow grain fields surrounding the town.

Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with a Reaper (1889)

Oil on canvas, 28 ⅖ x 36 ½ inches

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; Wikimedia Commons

While still in Provence the following July, van Gogh painted the lush expressionistic masterpiece Wheat Field with a Reaper that gleams with a swirling sea of grain in impastoed layers of yellow-orange with white highlights seen in many of his later Saint-Rémy paintings. A benevolent sun stands against a sky of aquamarine and seems to radiate from the canvas. The view is from the upper story of the building where van Gogh had sought recovery from depression and obsession, and shows the field’s gray-white boundary wall but without any sense of confinement. The painting was one among his final Harvest (Wheat Fields) ensemble of a dozen double-square, horizontal works that joined numerous other previously completed agrarian scenes including the masterpiece of harmonic yellows, creams, and greens featured in the Dayton exhibit, Field with Wheat Stacks.

The impassioned visionary wrote of its “vague figure toiling away… in broad daylight with a sun flooding everything with a light of pure gold,” as a modernist expression of “sacred realism” with calm, religious hope in the face of death. In describing another of his 1889 paintings, Evening: The End of Day, van Gogh made explicit reference to the influence of Millet’s Return from the Fields coupled with Breton’s verse “Return to the Fields” (which had been dedicated to Millet): “…The peasant twice browned / By the twilight and suntan / Forehead bathed in the pale light / Makes his way home, his labor done.”

The harmonious interweaving of van Gogh’s “ideal” religious faith and “real life” agrarian experience represented the mature spirituality the troubled artist had long been seeking. Art and religion—the lodestars of his life, converged in the fields beneath before him. Struggling to contain such revelation amidst the mundanity of daily affairs, he also realized its significance to art. Van Gogh’s embrace of a divinized nature celebrating spiritually aesthetic force swelled beyond his pastor father’s severe Protestant didacticism to embrace both humanity and the natural wonder of crops and trees and sky. He perceived the mission of preacher and painter alike to express the creative force evident in the humble truths of Christ’s parables and the expressive powers of form and color. Such grace pervades nature and everyday community experience without need for miracles, material possessions, or complicated doctrine.

Millet had become his “father” and “eternal master,” van Gogh had written to Theo in 1884, and had offered insight into his own motivation: “Painting peasant life is a serious business, and I for one would blame myself if I didn’t try to make pictures that could give rise to serious reflections in those who think seriously about art and life.” Van Gogh likened his sketches and studies to the sowing of seeds by a farmer but, “I long for harvest time” he explained to his brother, and labored over final works on canvas with knife and brush.

Van Gogh’s association of grain and sheaves with life suggested humanity’s vulnerability and resiliency. The passionate reds and golds of his art are composed in balanced synthesis with the greenery and browns of verdant earth. He complemented these colors by mysterious orange and blue tones of the cosmos—a palette strikingly seen in his The Resurrection of Lazarus (1890). Despite the susceptibility of grain to ruin from fire and wind, or harvest with scythe and sickle, the fields serenely endured as tangible evidence of incomparable beauty, fecundity, and energy of the divine order.

Vincent van Gogh, Field with Wheat Stacks (1890)

Oil on canvas, 28 ⅖ x 36 ½ inches

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Switzerland

Van Gogh expressed these beliefs to his sister, Wilhelmina, from Saint-Rémy in the summer of 1889: “What else can one do, when we think of all the things we do not know the reason for, than go look at a field of wheat? The history of those plants is our own; for aren’t we, who live on bread, to a considerable extent like wheat, at least aren’t we forced to submit to growing like a plant without the power to move, by which I mean in whatever your imagination impels us, and to being reaped, when we are ripe, like the same wheat?” The comment foreshadowed the artist’s increasing vexation and demise in the face of his own troubled soul’s harvest. The reaper as death fulfilled the sower’s purpose in the grand mysterious cycle of life and death seen in van Gogh’s beatified landscape where the finite and infinite coalesce.

The farmer motif is a profound and vital expression of life’s purpose, with figures cast differently from the plodding toilers in Millet’s paintings. Van Gogh’s harvesters are proud and purposeful workers whose faces shine with the luminous golden light that surrounds them and the grain. Reapers go forth blending into the contoured fields, gathering wheat and clutching sheaves as if holy ritual to feed heart and soul. Farmers, fields, and firmament are seen in throbbing, vital wholeness. Some of his magnificent harvest compositions like soothing imperial yellow and lavender Sheaves of Wheat and one in the magnificent Dayton exhibit, Field with Wheat Stacks (July 1890), present arrangements of nodding bundles and piles of stalks as if tender family portraits.

The softer palette of van Gogh’s later works was influenced by his high regard for the paintings of Impressionist leader Claude Monet (1840-1926). In popular discourse such works have been considered objects of enjoyment more than understanding, but plein air landscapes by Monet and Pissarro are more than passive depictions of location and light. Impressionistic views often show “fields of vision” selected for particular forms like sheaves, rows, and stacks of powerful meaning for artist and viewer.

Arles

Harvest at La Crau with Montmajour (June 1888) — VGM, Amsterdam

Haystacks in Provence (June 1888) — K-MM, Otterlo

Summer Evening in Arles (June 1888) — Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Switzerland

Wheat Field (June 1888) — Private Collection

Wheat Field with the Alpilles Foothills (June 1888) — VGM, Amsterdam

Arles: View from the Wheat Fields (June 1888) — Musée Rodin, Paris

Wheat Field with Stacks (June 1888) — Private Collection

Wheat Field with Sheaves (June 1888) — Honolulu Museum of Art

Harvest in Provence (June 1888) — Israel Museum, Jerusalem

The Sower (at Sunset) (June 1888) — K-MM, Otterlo

Saint-Rémy

Wheat Field with Reaper and Sun (June 1889) — K-MM, Otterlo

Wheat Field with Cypresses (June 1889) — MMA, New York

Evening Landscape with Rising Moon (July 1889) — VGM, Amsterdam

Wheat Field with Cypresses (September 1889) — National Gallery, London

Wheat Fields with Reaper at Sunrise (September 1889) — VGM, Amsterdam

Peasant Woman Binding Sheaves (September 1889) — VGM, Amsterdam

Reaper with Sickle (September 1889) — VGM, Amsterdam

The Reaper, after Millet (September 1889) — Private Collection

The Thresher, after Millet (September 1889) — VGM, Amsterdam

The Sheaf-Binder, after Millet (September 1889) — VGM, Amsterdam

Wheat Field with Cypresses (September 1889) — Private Collection

Wheat Field Behind Hospital (December 1889) — VMFA, Richmond

Noon: Rest from Work (January 1890) — Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Auvers-Sur-Oise

Wheat Fields with Reaper, Auvers (June 1888) — Toledo Museum of Art

Wheat Fields near Auvers (June 1890) — Belvedere Gallery, Vienna

Peasant Woman Against Wheat (June 1890) — Private Collection

Wheat Field under Clouded Sky (July 1890) — VGM, Amsterdam

Wheat Fields at Auvers under Clouded Sky (July 1890) — Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh

Wheat Field with Crows (July 1890) — VGM, Amsterdam

Field with Wheat Stacks (July 1890) — FB, Riehen/Basel

Wheat Field with Cornflowers (July 1890) — FB, Riehen/Basel

The Fields (July 1890) — Private Collection

Wheat Fields with Auvers in Background (July 1890) — Private Collection

Sheaves of Wheat (July 1890) — Dallas Museum of Art

Van Gogh Wheat Field Series Paintings, 1888-1890

FB: Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Switzerland

K-MM: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands

MMA: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York