There is much interest these days in “back to the land” efforts to reconnect folks with country life. It is encouraging to see examples here some rural communities in our area of sufficient revival evident in thriving local schools and main streets. Art historians remind us that life back in “the good old days” was not always that “good” for lots of folks, nor especially “sustainable.” Writings of medieval theologians confirm the view of many present-day researchers that European peasants were practitioners of extractive farming methods who were often deemed unworthy by the Church for anything other than servile labor to await reward in the hereafter. In the main, depictions of harvest from the Middle Ages do not show happy workers gathered together in fields of plenty. Reapers and gleaners still seen in the surviving stained glass, frescoes, and bas reliefs of great European cathedrals typically show a single individual or pair of field workers armed with sickle or scythe in tall, thin stands of grain. The expressionless figures are typically cast in larger theological “Labors of the Months” narratives as emblems of Christian suffering intended to impress parishioners with the need to toil ceaselessly throughout the year as sinful consequence of humanity’s fallen state.

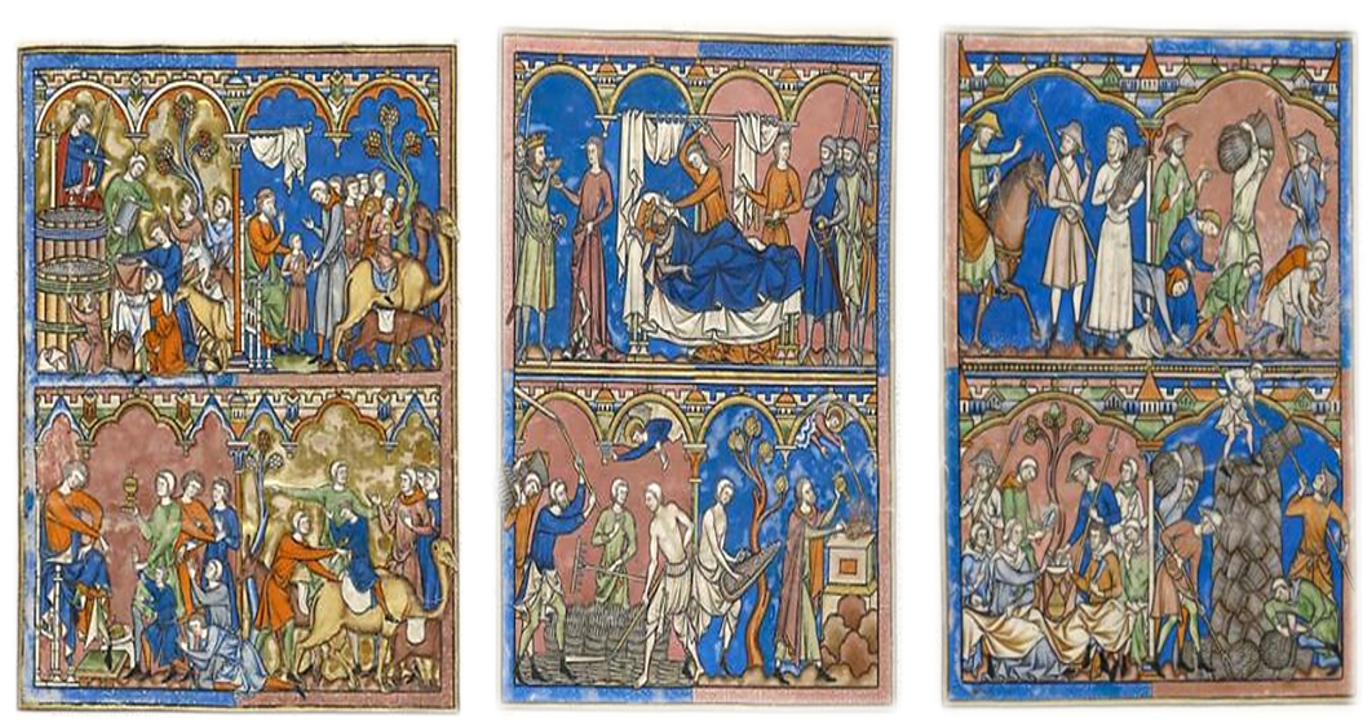

G. Freman, P[eter]P. Bouche (engraver), Boaz espouseth Ruth; From Richard Blome, History of the Holy Bible (London, 1688), 7 ⅛ x 12 ¾ inches

For three millenia the Old Testament Book of Ruth has been synonymous with the abiding theme of divine deliverance associated with gleaning, and served to inspire depictions of her and Boaz throughout the centuries from the vivid images of medieval illuminated manuscripts to the modern dreamy reverie of Surrealist Marc Chagall. The annual harvest of feudal times made possible the exchange of peasant labor for manorial protection and provision. Notions of upward mobility in moral or imaginative terms, therefore, are not found in the French Song of Roland, Slavic Tale of Igor’s Campaign, sermons of St. Francis, or visions of Hildegard of Bingen. (Hildegard did write, however, of the praiseworthy qualities of ancient grains like spelt and emmer.) The very constraints of social stratification fostered a degree of egalitarianism among serfs, who represented some 90% of the population, which significantly altered ancient Judeo-Christian concepts of gleaning intended to benefit the poor.

![G. Freman, P[eter]P. Bouche (engraver), Boaz espouseth Ruth; From Richard Blome, History of the Holy Bible (London, 1688), 7 ⅛ x 12 ¾ inches](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/577c39f56b8f5bec285fe33f/1551929267350-3QUNNT7OP9JJ5MJ3W4U6/RuthBoaz.jpg)