The Palouse Heritage Blog

Organic vs. Salmon-Safe vs. Conventional: What’s the Difference in How Grains Are Grown?

We are often asked if our grains are organic. Learn how our organic and Salmon-Safe Certified regenerative farming practices protect soil, water, and health — and why they’re a cleaner, safer alternative to conventional farming.

30th Anniversary Edition of Palouse Country is Released!

More Supply Chain Disruptions Threaten Global Food Security

New Research Uncovers Immense Value from Old Wheat Varieties

Heritage Grains Play an Essential Role in National and Global Security

Summer Reflections

Pendleton’s Umatilla County Museum and the Runquist Brothers

Amazing Aberdeen (Idaho) and the National Cereal Grains Collection

Cyrus McCormick and the Reaper Revolution

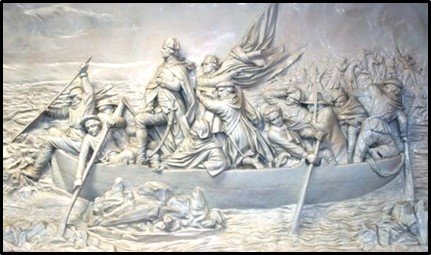

Founding Farmer Art and Architecture

Protecting the Common Good

Determining and Affirming Values of Care

Harvests Then and Now

Perilous Bounty vs. Golden Wheatfields

Of Hackles and Scutching— Old World Flax for New World Linen

Van Gogh’s Landscapes—Agrarian Beauty and Life’s Renewal

“Modern US Wheat Has Roots in Ukraine” - My Interview With NPR's The World

Daily Bread, Liberty, and the Orphans of Ukraine

Goodness, Grain, and Humankind— Thoughts Concerning Ukraine and Our Nation’s Founders