“A King’s Estate” and the Eleusian Fields

Anthropologist Clark Wissler observes that distribution of bread in ancient Egypt was the principal reason civil administration first developed, and that association of life-giving bread with spirituality has been a central tenet of western religions. Homer’s eighth century BC description of a summer harvest in the Iliad (Book 18) is remarkable not only for being the first known reference to grain harvesting in Western literature, but for aptly describing with spectacular imagery the method commonly used for cutting grain that continued well into the modern era. The account describes the magnificent shield forged by Hephaestus for Achilles that featured a microcosm of the Greek year including a recitation of cooperative summertime harvest labors.

Elsewhere in Homer’s epic the imagery of sickle, reap, and harvest is used for the familiar martial metaphor in ancient literature for weaponry, battle and death. The context of the episode is the Trojan attack led by noble Hector on Odysseus’ invading Greeks. A great shield is again featured, this time belonging to Hector, which blazed out “like the Dog Star through the clouds, all withering fire” in another allusion to harvest. The appearance of Sirius in the summer sky appeared at harvest time in the Mediterranean so was laden with great mythic significance given the prospect of abundance or disaster depending on such elemental conditions as pestilence and weather during the critically intense few weeks of harvest.

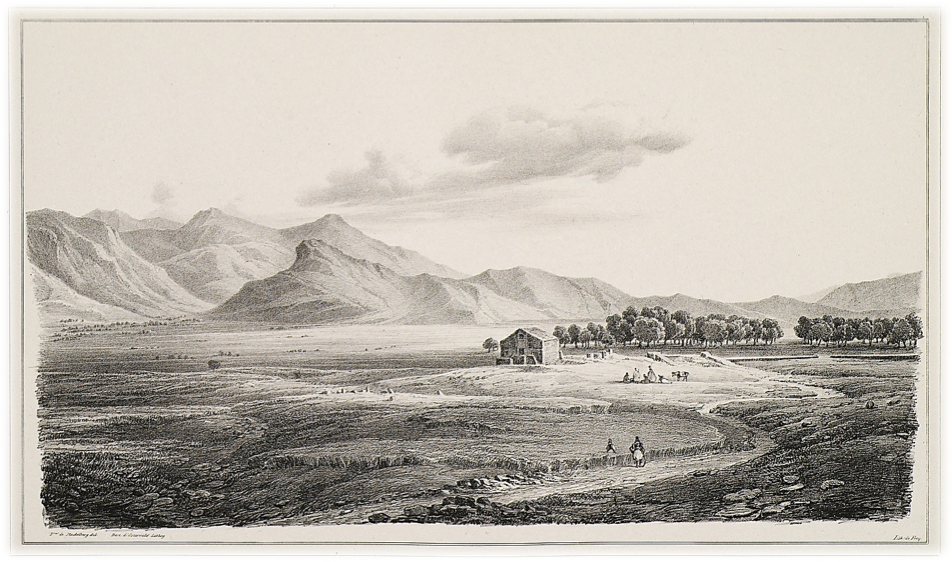

Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, Eleusian Fields on the Rharian Plain (Lithograph on paper, 9 ½ x 13 ⅗ inches), La Grèce: Vues pittoresques et topographiques (Paris, 1834)

In Greek mythology, Demeter (literally “Grain Mother,” Roman “Ceres”) related to humanity the means to domesticate cereal crops in the Eleusian Fields on ancient Attica’s Rharian Plain near Athens, legendary home of humanity’s first harvest. Demeter’s origin is mysterious as this maternal archetype was not native to the Greece mainland, but had been adopted into the Olympian pantheon with her etiological myth explaining seasonal change. Like her nourishing grains, Demeter had come from the eastern Mediterranean to share life-giving blessings at the dawn of classical civilization. She was kindred spirit to Phoenician Cybele and Egypt’s Isis—inspiration for Walt Whitman’s celebrated 1856 “Poem of Wonder at the Resurrection of Wheat.”

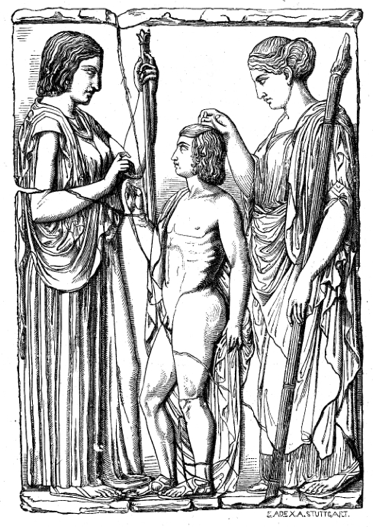

“Great Eleusinian Stele” of Demeter, Triptolemus, and Persephone (c. 440 BC). From the original Pentalic marble, 86 x 59 inches. Discovered at Eleusis in 1859, now at the National Archaeological Museum, Athens Otto Seemann, Grekernas och romanes mytologi (1881).

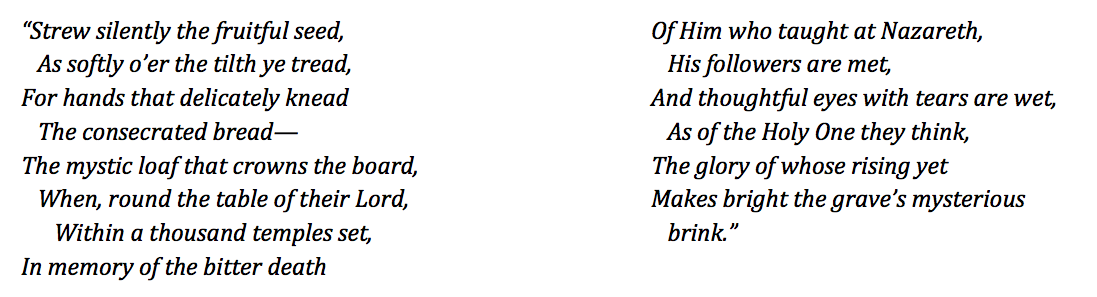

Demeter spurned wine at Eleusis for sacred kykeôn, the divine “mixture” of infused grain and herbs that strengthened the Iliad’s adventurers and refreshed Eleusian pilgrims at autumnal rites practiced in Athens and elsewhere from at least 800 BC to 300 AD. The ancient myths had both spiritual and terrestrial dimensions that tempered humanity’s martial tendencies. “History celebrates the battlefield wherein we meet our death,” French naturalist Jean-Henri Fabre observed (1918), “but it scorns to speak of the plowed fields whereby we thrive.” American Romantic poet William Cullen Bryant expressed the theme of deliverance through divine sacrifice in “Song of the Sower” (1864).

Sacred virtues of self-sacrifice bring renewal and sustain the spirit; and the practical science of tillage, seeding, and harvest sustains the body and demands the discipline of timely labor. Democratic Athens was heavily populated and reliant on trade in grain to provision its populace. Aristotle, Demosthenes, and other ancient sources contain considerable reference to state supervision of wheat and barley prices, the special status of Athenian magistrates responsible for the grain supply (sitophulakes), and recurrent priority of such matters on the Assembly’s agenda. Visual depictions of grain harvests and other farming endeavors on sculpture, vases, or other forms, however, are paradoxically rare which suggests that those who could afford such luxuries had greater decorative interest in heroic myth than in idealized or realistic country scenes.