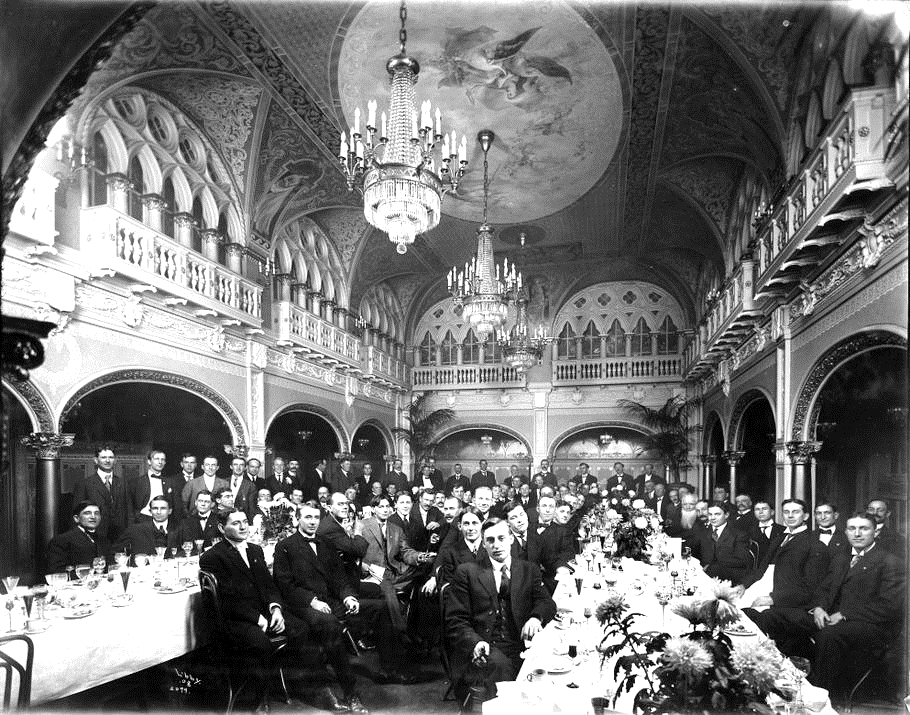

Next stop of agricultural interest on our summer road trip was Springville, Utah. Founded in 1937, Springville’s acclaimed Museum of Art Soviet and Russian Collection holdings are among the nation’s most extensive for rural subjects that include numerous harvest scenes painted in the 1890s by members of the Church of Latter-day Saints Paris Art Mission. I thank docent Judy Mansfield for helpful information on the remarkable story of the museum’s vast holdings. Springville’s Soviet and Russian Collection began unexpectedly in 1989 when museum director Vern G. Swanson first embarked on a series of trips to the USSR on behalf of the Grand Central Art Gallery Education Association. Swanson met Russian artist Vladimir I. Nekrasov (1924-1998) of Moscow’s Surikov Art Institute who introduced him to important works of Russian Expressionism and Social Realism that led to a major exhibition at Springville in October 1990 and eventual artwork purchases for the museum.

Springville Art Museum; Springville, Utah

Mahlon Young, The Farm Worker (1938)

Successive assaults upon the Soviet Union’s rural populace in the 1920s and ‘30s involved Stalin’s brutal campaigns to collectivize agricultural lands and against religion that led to widespread violence and famine. Millions of peasants perished or were displaced from their native villages through the imposition of these policies to abolish private property and modernize the economy. Russia remained a major producer of grain until this period which witnessed the expropriation of commodities from landed peasants (kulaks) who had withheld harvests in order to boost prices. Stalin’s push to industrialize the country at all costs required the provisioning Soviet cities, agricultural mechanization, the mass murder and exile of kulaks, and the exodus of vast numbers of younger rural residents to urban areas. The impact of these forces was devastating to traditional Russian village life and crop production. The nation was plunged further into cataclysm after war with Germany commenced in 1941.

As people and landscapes suffered, authors and artists sought memory for solace as well as lament. The glorification of communist principles through state-sanctioned Socialist Realism governed official Soviet art and literature from the 1930s to 1980s. Muscular representations of urban and rural life that lauded labor and socialist ideals generally characterized the approach, but later strains featured honest views of everyday life reminiscent of the French Impressionists and Taos Expressionists. Marx had viewed artists and writers as valued members of an intellectual vanguard promoting revolutionary change. Leon Trotsky later wrote in Literature and Revolution (1924) that their insights revealed the nature of society and if freely expressed would help guide the revolutionary struggle. Stalin, however, had no tolerance of art for art’s sake. His authoritarian policies sought conformity and denigrated individuality—the basis of creativity.

Konstantin Topuridze, People’s Friendship “Golden Sheaf” Fountain (1954)

Exhibition of Economic Achievements, Moscow; Wikimedia Commons

Unless about earlier periods or other places, Soviet depictions of internal discontent and tragedy were forbidden in favor of sentimentalized worker characterizations of the proletarian dream. The character of Soviet monumental art was famously exemplified in Vera Mukhina’s 80-foot steel sculpture Industrial Worker and Collective Farmer (1936) that was built to crown the Soviet pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris. Plated in radiant chrome-nickel, the massive female figure designed by Mukhina (1889-1953) grasps a sickle alongside her hammer-wielding companion in striding poses that symbolized the nation’s aspirations. After the Paris fair, the sculpture was relocated to the entrance of Moscow’s sprawling All-Union Agricultural Exposition on the city’s north side where substantial halls showcased numerous aspects of crop, livestock, and food production. Architect Konstantin Topuridze (1905-1977) designed the enormous Golden Sheaf (People’s Friendship) Fountain (1954) as one of the park’s centerpieces that features a towering grain sheaf encircled by three colored glass cornucopias and sixteen bronze statues of young women who symbolized the Soviet republics. (In 1959 the complex’s name was changed to the Exhibition of Economic Achievements and has come to include a grandiose amusement park, year-round trade shows, concert hall, and pavilions featuring space exploration and technological advancements.)

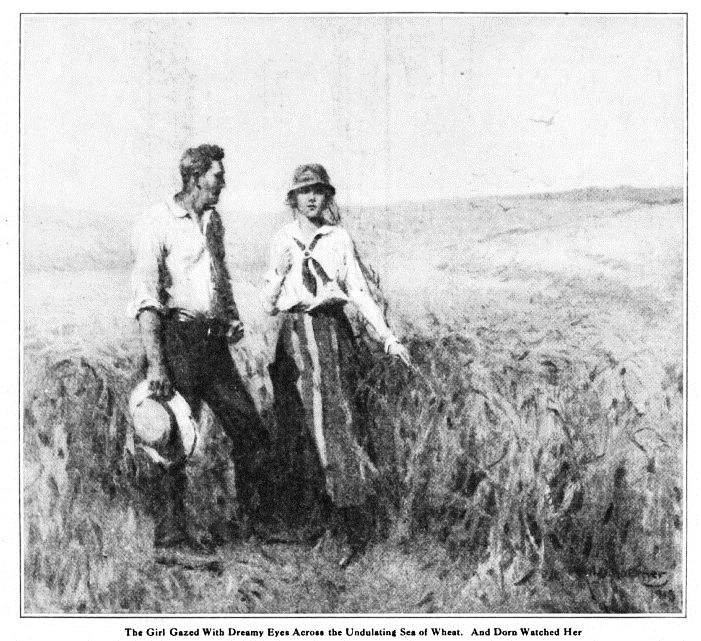

Idealized paintings of country life like Arkady Plastov’s Harvest Festival (1937) and Field after Harvest—Sheaves (1954) by Yuri Kugach show bountiful fields and smiling brigades of kolkhoz (collective farm) laborers clad in red neckerchiefs and head scarves enthusiastically driving farm equipment or tending threshing operations. Plastov, born to a family of icon painters near Simbirsk on the middle Volga, also painted works like Harvest (1945) and Spring (1954) that risked official condemnation given his Impressionistic renderings of commonplace scenes devoid of political sentiment. Harvest is a discomforting view of an aged reaper sharing a meal in the field with three children scarcely old enough to shoulder such responsibilities. Completed in the last year of a war that had inflicted enormous suffering throughout Europe, the scene also inspires appreciation for the home front brigades of women, children, and the elderly who labored for years to sustain soldiers and civilians. Plastov’s dynamic, colorful Haymaking (1945) shows a shirtless teen flanked by two elderly men and a woman who cut grass near a copse of birch trees.

Kugach, who settled in the Tver countryside after the war, went on to establish the Moscow River School in 1974 to revive the dramatic style of Repin, Levitan, and other Russian Realists. Ambidextrous painter Nikita Fedosov (1939-1992), Yuri Kugach’s nephew, became a prominent member of the group and painted numerous country scenes including Last Rays and Overcast Field (1966). Muscovite Victor Ivanov studied with Kugach at Moscow’s Surikov Institute of Art in the late 1940s and in the 1960s became a leading member of the Avant Garde Severe Style that depicted the grim austerity of post-war Soviet life in opposition the naïve depictions of Socialist Realism. Artists like Ivanov risked establishment censure but painted throughout the Khrushchev reform era in ways that recalled the 1910s Futurism of Kazmir Malevich and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. Ivanov painted numerous harvest scenes like Harvesting near Ryazan, Men Resting at Harvest, and Women Harvesting (1965). These spare, balanced compositions in irregular blocks of olive, mustard yellow, and chestnut contrast rural toil with the rustic beauty of the Russian countryside.

Dmitry I. Slobodin, Untitled Donbas Harvest Scene (1982)

Gouache on paper, 17 ¼ x 22 inches

Columbia Heritage Collection

A native of the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine, Dmitry I. Slobodin (1929-2005) graduated from the Art College of Lugansk and became a master of Impressionistic palette-knife paintings in tempura and oil earth tones that depict the quiet beauty of his native land while resisting the artificiality of the regime’s officially sanctioned Socialist Realism. Slobodin’s untitled Donbass Harvest (1982) shows mottled field rows of tawny cream with shadowed forest greens beneath a gleaming orange ribbon of setting sun. At left far in the distance beyond a darkened tree-lined swale one can almost hear the hum of a late model Rostelmash self-propelled combine throwing a roiling cloud of yellow-white chaff. The red machine appears to be opening up a field of ripened grain at day’s end near at base of a broad gentle slope in a scene of bounty and peace.