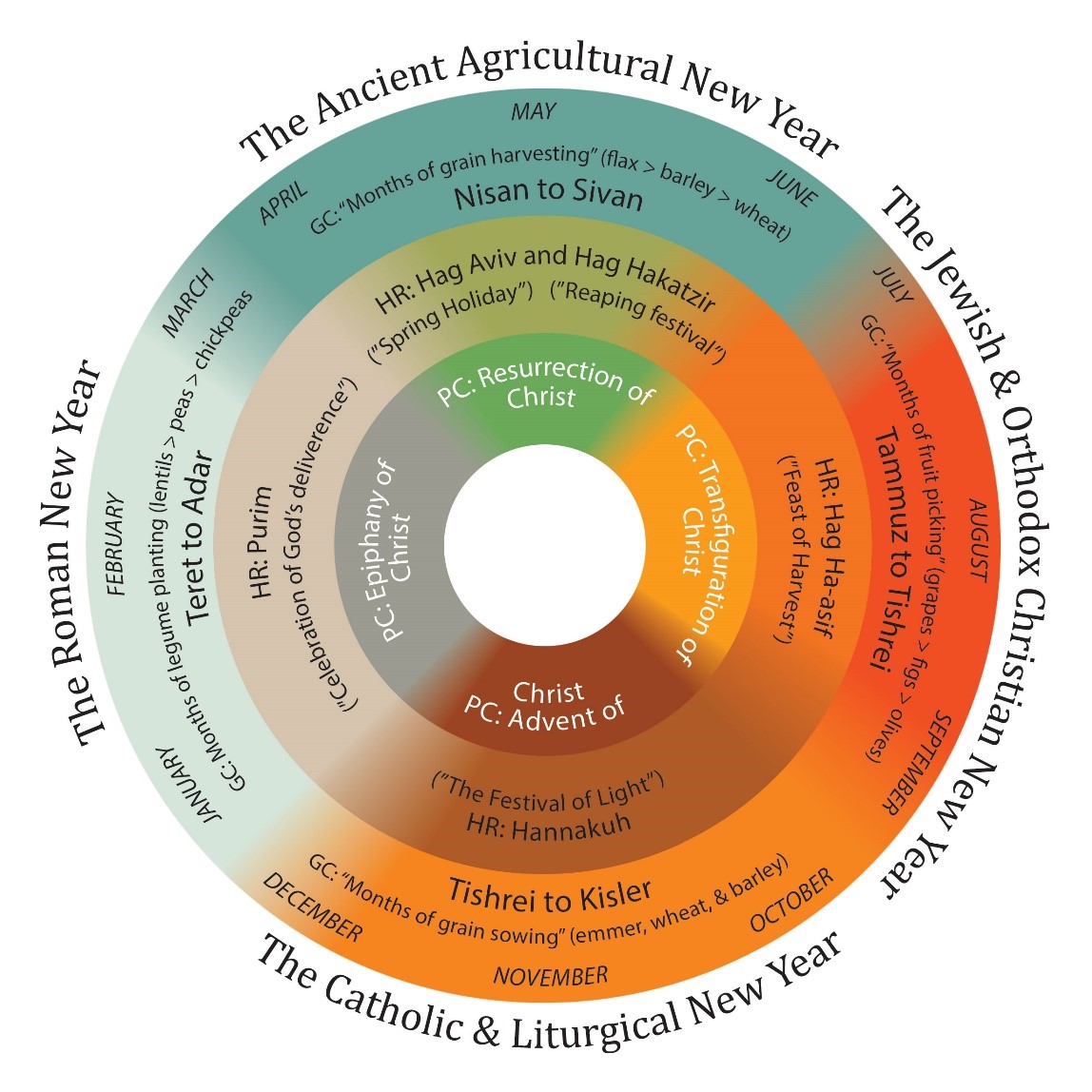

You shall keep the Feast of Unleavened Bread…, and the Feast of Harvest, the firstfruits of your labors which you have sown in the field; and the Feast of the Ingathering at the end of the year, when you have gathered in your labors from the field. --Exodus 23:15-16

Harvests in, the weather cools, colorful leaves swirl about, and Thanksgiving’s approach turns thoughts to family gatherings, feasting, and football games. Growing up on our small farm in eastern Washington’s Palouse Country, our Thanksgiving was one of the few times we left home to journey a hundred miles north toward Canada to our maternal grandparents remote home in the thickly forested Pend Oreille highlands. To this day Grandma Peterson’s bread and pork dressing with grated carrots and beets lives on as a favorite holiday recipe. A very devout soul, she personified thanksgiving and shared the bounty of their substantial gardens—as well as hand-me-down children’s clothes, firewood, baked goods, and other necessities—with families near and far. Thanksgiving’s approach has led me to think again about the holiday’s origins in ancient times and its association with early American history.

Harvesting Palouse Heritage “Eden Amber” (2021)

An Heirloom Mesopotamian Hard White Bread Wheat

Old Testament Israel’s Feast of Harvest (Shavuot), one of nation’s three principal holidays, was a joyous event celebrated in Jerusalem on the fiftieth day after Passover. Blessed with favorable Mediterranean growing conditions on the Plain of Esdraelon and in nearby fertile valleys, the ancient Hebrews’ barley harvest generally commenced with the beginning of the dry season in April and early May, followed by the gathering of wheat and lentils into June. The fiftieth-day spring harvest festival, also known as the Feast of Weeks (later Christian Pentecost), marked the completion of the grain harvest season and commemorated divine provision for the people with Promised Land bounty.

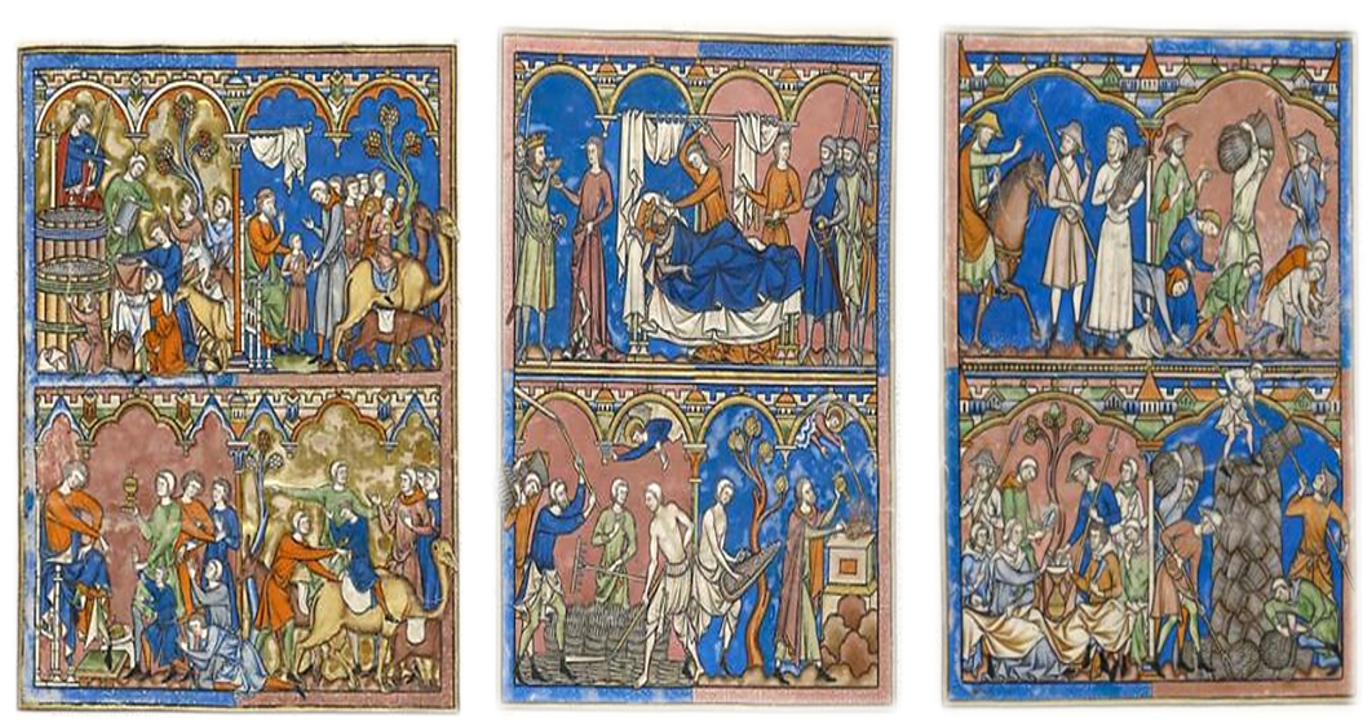

The subsequent Feast of Ingathering was held in Jerusalem several weeks later to celebrate harvest of olives, grapes, figs, and other fruits. It also involved Temple offerings of sheaves, bread, and flour for the priests, recitation of the Hallel psalms (113-118) and readings from the Book of Ruth, joyful dances, and splendid communal feasts. Historians Douglas Neel and Joel Pugh note that activities associated with these holidays and the biblical context of their pronouncements offered two important themes to Jewish and later Christian observers: thanksgiving for divine blessing and a bountiful land, and the resulting social responsibilities to the less fortunate.

Cultures throughout the world have commemorated the life-giving blessing of harvest throughout recorded history with traditions evident in religious ceremonies and stories handed down through the generations. According to Jewish folklore, Noah’s resourceful wife resorted to unique combinations of ingredients as the Ark’s provisions dwindled near the end of its voyage. What in Turkish cuisine is known as “Noah’s Pudding,” or ashura, customarily features various sweet mixtures of pearled barley and bulgur wheat with beans, chickpeas, dried fruits, and nuts. Nutritious black emmer has been called “Prophet’s Wheat” from a tradition suggesting Noah fed it to animals on the Ark. Black emmer was one of many Middle Eastern grains introduced to the Pacific Northwest in the 1890s by legendary USDA “plant explorer” Mark Carleton who sought varieties from regions throughout the world with climates and soil conditions similar to various areas of the Columbia Plateau.

Contemporary Wheat Weavings

Fern Enos; Colfax, Washington

Traditions honoring the vitality of grain perpetuated the Old World craft of wheat-weaving with artfully twisted shapes are still featured at county fairs throughout America. Agrarian folklorist Rene Peschel traces the origins of Northwest wheat-weaving to the 1974 centennial commemoration of Mennonite immigration to Kansas from Russia. Midwestern Mennonite women wove mementoes with Russian “Turkey” Red wheat and the following year Moses Lake resident Phyllis Franz learned the skill from a Mennonite visitor the area and taught it to members of her fellowship and other friends. One of the most spectacular examples of the craft is the life-size “Wheat Lady” (1997) by Aileen Warren and Jackie Penner of Dayton, Washington. The pair wove a grain dress from 225 feet of wheat straw and embellished the effigy with over 900 hand-tied decorative knots and 2500 heads of wheat.

Aileen Warren and Jackie Penner, Wheat Lady “Corn Dolly” (1997)

Straight and braided straw with 2500 heads of wheat

Washington Association of Wheat Growers

![G. Freman, P[eter]P. Bouche (engraver), Boaz espouseth Ruth; From Richard Blome, History of the Holy Bible (London, 1688), 7 ⅛ x 12 ¾ inches](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/577c39f56b8f5bec285fe33f/1551929267350-3QUNNT7OP9JJ5MJ3W4U6/RuthBoaz.jpg)