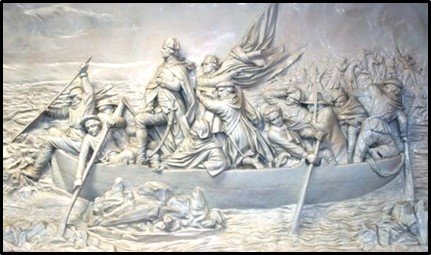

Cabrini Brothers Plaster Bas-Relief (c. 1910)

After Emmanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851)

Endicott-St. John Middle School; Endicott, Washington

How happy to think to our self when conscious of our deeds, that we started from a principle of rectitude, from conviction of the goodness of the thing [freedom] itself, from motive of the good that will come to humankind.

—Thaddeus Kosciuszko to General O. H. Williams; February 11, 1783

Day after day throughout all twelve years in the stately three-story brick school in rural hometown Endicott, notable figures from America’s past stared down at us from each classroom in the form of substantial bas-relief sculptures. Bearing the incised manufacturer name “Caproni Brothers” of Boston, these substantial plaster works resembled carved marble and spoke to the value placed on public education and art by members of our farming community who built the school in 1911. The three largest Caproni masterpieces hung against a wall of the third floor auditorium and included the famous scene Washington Crossing the Delaware which was painted some seventy years after the event by German-American artist Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze (1816-1868). The painter had returned for a time to his homeland and sought to support the wave of democratic revolts against European monarchies in the late 1840s. Leutze painted several other American Revolutionary War views including Mrs. Schuyler Burning Her Wheat Fields (1852) which is now held by the Los Angeles County Art Museum.

Notable battles that changed the course of world history were famously fought on fields of grain including Caesar’s defeat of Pompei in 48 BC on Greece’s Thessalian Plain at Pharsalos (Farsala—birthplace of Achilles), and English King Henry’s victory over the French at the Battle of Agincourt (1415) during the Hundred Years’ War. That large military engagements took place across vast rural areas is unsurprising and came to be associated with heroic sacrifice and symbolic harvests of souls. The Schuyler Wheatfield scene is especially notable for depicting an incident associated with the 1777 Battle of Saratoga that is considered the turning point of the Revolutionary War.

We learn in school about the nation’s Founders—men and women like Washington and Jefferson, John and Abigail Adams, James and Dolly Madison, Benjamin Franklin, and others who pledged their “sacred fortunes” to procure a free if imperfect nation based on democratic values. As part of this effort begun nearly 250 years ago other influential names are also familiar—army heroes Marquis de Lafayette of France, and stern Baron von Steuben of Prussia who became General Washington’s Chief of Staff and helped bolster patriot forces amidst the baleful conditions of Valley Forge. Another formidable if lesser-known foreign officer in freedom’s cause was cavalry general Thaddeus Kosciuszko (ko-choose-ko) who played a leading role in the Continental victory at Saratoga.

Emmanuel Leutz, Mrs. Schuyler Burning Her Wheat Fields (1852)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Painting at the distance of many decades, Leutze took liberties for his masterpieces of patriotic romanticism and the dramatic view of harried Catherine Schuyler, wife of Continental General Philip Schuyler and in-laws of Alexander Hamilton, combines elements of fact and legend. She is shown clad in red, white, and blue setting fire to a field of wheat on the family’s Hudson River estate presumably in September of 1777 to prevent its harvest by British troops approaching in the distance. The subsequent defeat of British General Burgoyne at the nearby Barber Wheatfield during the Battle of Saratoga in early October is considered the turning point of the American cause. The painting is remarkable not only for its depiction of a female figure in heroic wartime action, but she is shown being assisted by an African-American boy who carries a metal lamp.

Kosciuszko was a Polish nobleman and idealist, whose own privileged position in life contrasted with the democratic values he came to champion in peacetime and war. Commissioned a brigadier general by the Continental Congress and later made a member of the American Philosophical Society through Benjamin Franklin’s support, Kosciuszko nevertheless returned to Europe and helped lead the fight against autocracy in Poland as well as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in the 1790s. Russia with far superior forces under Catherine the Great eventually prevailed against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Turks in order to gain strategic access to the warm water Black Sea ports. Russia emerged victorious in 1792, and two years later Empress Catherine herself initiated the founding of Odessa which soon became Russia’s third largest city. Russia’s roots in Ukraine stretch back much further as Kyiv is considered Russia’s founding capital and flourished in a cultural Golden Age from the 10th to 12th centuries until its devastation in 1240 by the invading Mongols.

To secure her vast newly acquired southlands from such foreign threats, Catherine instituted one of the largest and most diverse settlement campaigns in European history. Substantial numbers of Armenians, Greeks, Italians, and other ethnic groups were directed to Ukraine to live among native Crimean Tatars and Turkic peoples. Beginning in the 1760s Catherine arranged for the relocation of 27,000 peasants from her native Germany to the lower Volga region, and some 50,000 followed until the 1830s to establish Black Sea colonies throughout Ukraine. Many came in the aftermath of Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion of Russia in 1812 that inspired Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace. A century later the prolific Black Sea German colonists needed more land to farm and faced increasing cultural threats from ascendent Slavic influences. Some chose to relocate as their ancestors had done, and many found new homes in America’s fertile farming districts—the Chesapeake Peninsula’s red loam country of Maryland and Delaware, southeastern New York’s “black dirt” area, the vast Midwest’s Great Plains, Pacific Northwest’s Columbia Plateau, and Canada’s prairie provinces. Black Sea German Mennonites brought Crimean “Turkey” Red wheat seed to Kansas in the 1870s which revolutionized American grain production and breadmaking.

Massey-Siemens Family Black Sea German Samovar

(c. 1890)

Palouse Heritage Collection

Those who appreciate this heritage have important reasons to be grateful their ancestors emigrated. European borders closed in 1914 with the outbreak of World War I, the Communist Revolution and three-year Russian Civil War followed until 1921, and Stalin’s brutal war on religion and campaign of collectivization led to Ukraine’s catastrophic Holodomor that claimed some eight million lives in the 1920’s and 30’s. Hitler’s invasion of the USSR caused the death of 27 million people during World War II. (American World War II casualties were about one million.) No wonder Timothy Snyder’s excellent 2010 chronicle of this era and place carries the disturbing title Bloodlands.

Eastern European immigrants and survivors came, and substantially remained, because Americans both new and old found fidelity in the ideas expressed in Kosciuszko’s 1783 letter about “deeds,” “principle,” “conviction,” and “goodness.” These terms may be variously debated today, but they did not have vague meanings to those who wrote or heard them. And while they have been lived out in ways that excluded many since the nation’s founding, they have provided a framework for freedom, security, and economic prosperity unknown on a national scale in previous history. Such core ideas are threatened today because of extremism on both sides of a political continuum that values personal benefit and perceived “rightness” above the common good—an inversion of American First Principles.

To be sure, Jefferson’s expression “pursuit of happiness” is eighteenth-century code talk for private enterprise which forms the basis of modern economic development. But in the same breath he writes of “promoting the general welfare” since he, Kosciuszko, and the Founders understood liberty to be the use of freedom to promote national wellbeing, versus licentiousness as use of freedom for selfish power and gain. The peoples of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus faced a momentous decision in 1991 when in the wake of the USSR’s collapse they voted to declare independence. Much has been written about the litany of events and political vacillations that have ensued since then. May the cause of Kosciuszko yet prevail on both sides of the Atlantic, and peace and prosperity return to the people of Ukraine’s fertile Black Earth grainlands.