Who We Are

We are Palouse Heritage, a venture aiming toward the reintroduction of landrace grain flours and malts, grown here in the Palouse Country, for health, hearth and heritage. Some here may know the story of the Volga Germans, as some of you are surely kin, and it is difficult for me to say who we are without recalling from where we first came.

In the 18th century Catherine the Great, Tsarina of the Russian Empire, extended an invitation to foreigners to possess, inhabit and cultivate the fertile lands of Southern Russia that would later claim the title of the breadbasket of Europe. Our story follows a number of pioneering families who, considering the opportunity, ventured from their homes near and around Frankfurt Germany to make their new lives in Russia. Here they would fashion their lives much as they did in Germany, doing what they knew best, tending the earth and raising crops. As political instability and religious persecution loomed heavy by the 19th century, these humble farmers looked yet again toward new horizons that, by the 1880's, would lead them to the great northwest.

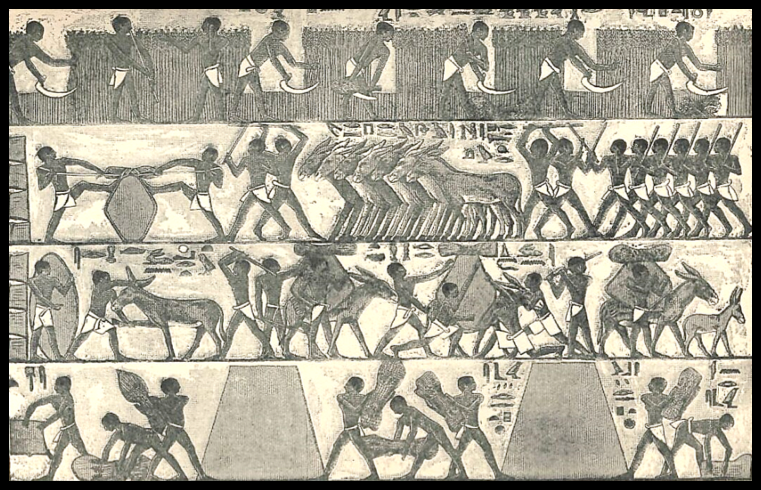

Led by a vanguard traveling by wagon and rail to Northwest destinations in the 1880s, members of the Ochs, Scheuerman, Kleweno, Litzenberger, Pfaffenroth, Schmick, Helm, Weitz, and other families would find their solace at "The Colony." The Colony, as they fondly referred to it, soon developed into a thriving settlement that provisioned families coming from the Old Country to their new home on the Palouse. Scores of new arrivals stayed while adjusting to life in the new land, and today many thousands of residents in the Northwest and beyond can trace their origins in the country to this time of sanctuary along the placid Palouse. Parents described it as a “Land of Milk and Honey” for children who tended the colony’s dairy herd and raided bee hives along the river. The newcomers used farming methods of medieval origin—long, narrow Langstreifen fields (akin to English furlongs) in three-crop rotations (Dreifelderwirtschaft), a shared “commons” (Almenden) for grazing and gardens, and harvests with sickle and scythe. In 2015, descendants of the Ochs and Scheuerman families reestablished The Colony as Palouse Colony Farm and tend now to the land our ancestors once did.

What We Do

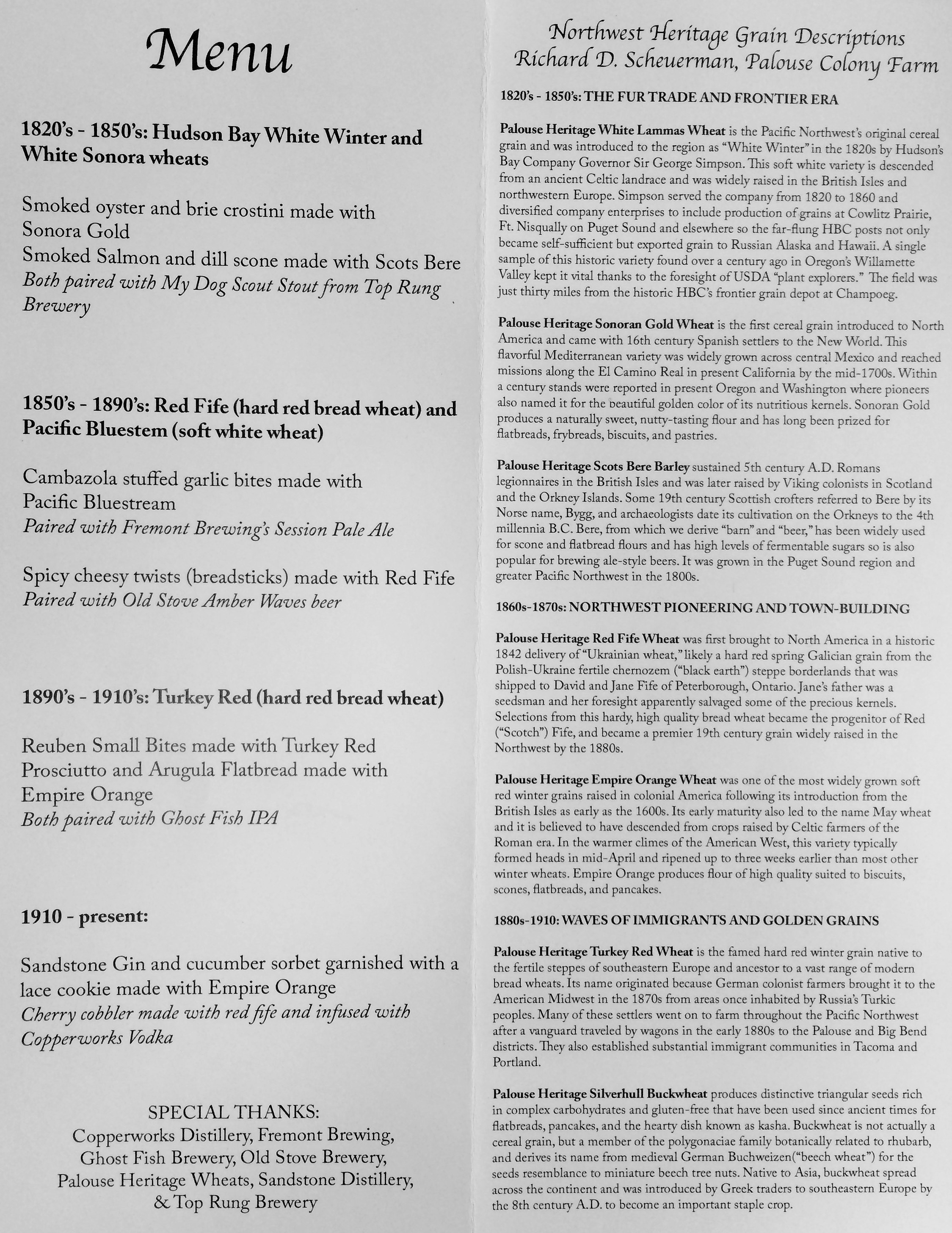

We aspire to capture the sentiment of the "commons" once again in a modern and complex era. Though, before anything can be done, we must first grow grains. At Palouse Colony farm we grow landrace grains or, as I am fond of saying, "we grow the grains God made." These landrace grains are ancient pre-hybridized varieties ("races") of wheat, barley, oats, rye, and other grains which nature has caused to flourish in areas ("lands") throughout the world where they adapted to local environmental conditions. Genetic diversity and natural selection have conditioned these landrace varieties to be remarkably resilient and quick to adapt to new locations. Through often painstaking efforts we have found, reintroduced and caused to flourish many of the landraces which the very progenitors of our blood had grown in the soil of which we are now stewards. Varieties like Palouse Heritage White Lammas, known to history as "Hudson's Bay Wheat," originated as a landrace in the Celitc Aisles and is the original cereal grain of the Pacific Northwest. Palouse Heritage Red Walla Walla is a soft red landrace wheat hailing from Great Britain that was sown and thrived from Walla Walla to the Palouse after 1890. Palouse Heritage Bere Barley is a landrace from the Orkney Islands and the "grain that gave beer it's name." Palouse Heritage Purple Egyptian barley is a hulless, glassy purple barley with its heritage in Egypt and raised by our Russian ancestors in southern Russia. The list goes on. At Palouse Colony Farm we aim to reintroduce the flavorful spectrum of these lovely forgotten varieties along with their tremendous health benefits back onto the northwest dinner table. Through cooperation and partnerships with area malters, millers, bakers, brewers and distillers, we aim to offer our kaleidoscope of grains in the form of healthy flours and delightful beverages, bringing something truly unique to the market place, while tending the land responsibly and sustainably.

Why We Do It

The pioneers and explorers of our area embraced a sentiment of community, their lives and livelihoods were often predicated by it. The experience of the entrepreneur strays very little from this idea; leaning on friends, neighbors and partners to the end of reciprocal benefit. Borrowing from contemporary agrarian visionary Wendell Berry, having a neighbor is preferable to having his land. In this sense we like to place ourselves in the boots of our pioneer forebears; inviting others of like mind to co-opt in the prospect of mutual success, in the pursuit of “the commons” while sharing common cause in health, community, relationships and sustainability. We revere the memory of things worth remembering and the preservation of things worth preserving. We do it to create sustainable grain economies that seek to respectfully feed body, mind, and spirit.

We do what we do for success, not just for ourselves, but for those around us. We do what we do to make real for others what we have known and what is continually revealed to us; that we live in a remarkable earth with spectacular diversity and creativity—the hallmark of our Creator—and what’s more is that it was meant for us. For health. For hearth. And for heritage.