Richard Scheuerman grew up about two miles from a farm known as the “Palouse Colony,” a farm between Endicott and St. John that was settled by German immigrants from Russia in the 1880s. “It was kind of a legendary place as a boy growing up,” said Scheuerman. Scheuerman said he was always interested in knowing more about the people there. “I enjoyed talking to older people. Even as a boy, I started visiting with elders of my grandfather’s generation who lived there,” he recalled. “It was all just very fascinating.” Scheuerman found himself learning about the “Old World agrarian methods” these farmers brought with them. It was a history he became hooked on. A recent business endeavor has brought Scheuerman to re-establish the Palouse Colony and its Old World farming methods as Palouse Heritage. “An opportunity came for us to acquire the property about two years ago,” said Scheuerman. “I have always kept interested in researching about the Palouse country. It was a special opportunity I didn’t want to pass up.”

Richard’s wife Lois and his brother Don Scheuerman are also part of restoring the Palouse Colony Farm, as is Rod Ochs. The Scheuermans and Ochs are all descendants of families who once lived at the farm. Richard said those involved in helping to restore grain varieties have been Alex McGregor, the McGregor Company and Andrew Wolfe, his nephew. Additionally, farmers Joe Delong of St. John, Tom Schierman of Lancaster and Chuck Jordan of Winona have helped. Richard called the effort so far “a learning experience.” “We’re always finding new things,” he commented. “It’s been a wonderful adventure just learning about this. It’s kind of all coming together.”

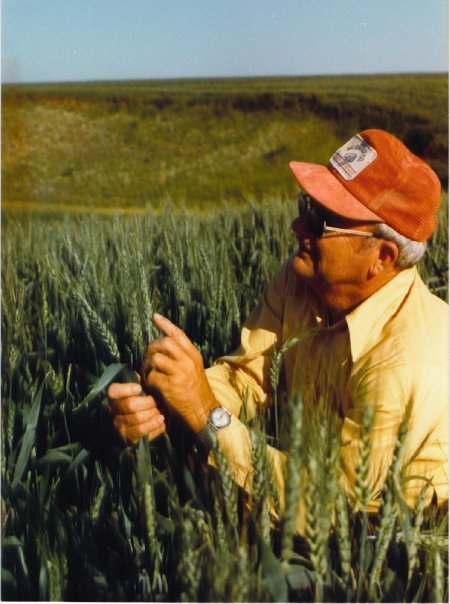

Richard told of how the German immigrants brought grains with them from Russia, including Turkey Red, a form of hard red winter wheat. Prior to the introduction of Turkey Red, soft white wheats were mostly used in bread production in the Pacific Northwest. “Until immigrants came from Russia, people made bread out of the soft winter wheats,” said Richard. “The Turkey Red revolutionized this. Virtually all breads today are made from hard red wheats.” Richard called the flavor of the grains now being grown again at the Palouse Colony “very distinct.” “The flavor is incredible,” he said. “We’re calling it ‘flavorful authenticity.’” Bringing back different grain varieties has been an experience right out of history, Richard said. “None of these have been grown for probably a century,” he said. “We’re seeing this unfold as living history, and friends are bringing out old recipes that were handed down.” Richard said they are not seeking to replace “modern hybrid” grains, but said there is a place for both. “Modern hybrids produce higher-yielding crops,” he said. “There’s a place for both worlds with markets internationally and with distinct flavor grains.”

Richard said that Don is also working on brews. “Don has been interested in the malting grains. He’s working with some craft malters and brewers,” said Richard. The brews are not quite ready, though. “The malt grain is being used in Spokane to create craft brews,” said Richard. “We’re trying to decide if we are ready to scale it up to production. It certainly tastes wonderful.” There are 40 acres on the property that are being farmed now. Richard said the property was also recently designated as a state historical site. The flours Palouse Heritage is developing will be available in December, and the availability of the brews will be announced at a later date. To learn more about what Palouse Heritage is doing and the history of the Palouse Colony, go to www.palouseheritage.com.

Article courtesy of The Whitman County Gazette