Contemporary agrarian art and literature offer insightful if variable perspectives on the transformation of rural landscapes and ways of country life. Stories and paintings can be elegiac and abstract as well as hopeful, with expressions of agrarian renewal evident in newfound appreciation for regional heritage and stewardship of the land. These considerations juxtapose values related to the natural world with those of private development and global capitalism. There is little to regret about archaic rural prejudices, grinding aspects of exhaustive dawn to dusk farm labor, and highly erosive tillage practices that once characterized areas like the Palouse. Small town redevelopment efforts are examining in new ways how local stories, specialty crops, and other resources might be shared to better contend with shifting labor patterns and demographic change. Harvest bees and church benefits still aid neighbors in times of special need. At the same time the annual harvest experience requires seasonal urgency, and the instinct for necessary provision unites humanity worldwide through rituals of planting and harvesting and thanksgiving.

Reflecting on contemporary agrarian experience, my longtime friend and novelist Bruce Holbert observes that in places like the Palouse, “God is in the details—turning a wrench, discing the summer fallow, spraying and rod-weeding, planting and cutting.” He considers these to be prayers “of the ancient sort, the ones you offer not for an answer as much as to be heard. Their reward is the opportunity to perform similar acts tomorrow and the next day. Their faith is not invested in an end; it is the opposite, a prayer to continue and in it is a kind of patience with the fates that few outside this place share.” The inhabitants of Holbert’s stories are not portrayed to explore the classic American theme of personal freedom amidst the conformist mainstream. Instead, they seem to take for granted a life of mystery and misery amidst economic hardship and the vagaries of nature, and speak perceptively from deep within as they move about in clouds of uncertainty. Holbert explores the abiding toil and periodic terrors of country life in Hour of Lead (2014), winner of the Washington State Book Award for Fiction, and in other novels and writings. His short story “Ordinary Days,” in which the Mason Hills are cast for the Palouse, features an exploration of rural change and meaning-making.

Nostalgia for some halcyon past contributes to the popularity of rural art but tempered with consideration of what has been lost and what has been gained. These contrasting themes are considerably explored in contemporary photographic art and are the special interest of Pacific Northwesterner John Clement and Don Kirby of Santa Fe. Ambivalent considerations about such trends are expressed in “Palouse” by Lewiston, Idaho, poet William Johnson:

There is always an empty house

by the road at the edge of town,

its windows whiskered with lilac

and letting in rain. Nearby,

a barn drags itself home,

and in May, daffodils trim the yard

against an ocean of wheat

that rolls in on a slow inexorable tide.

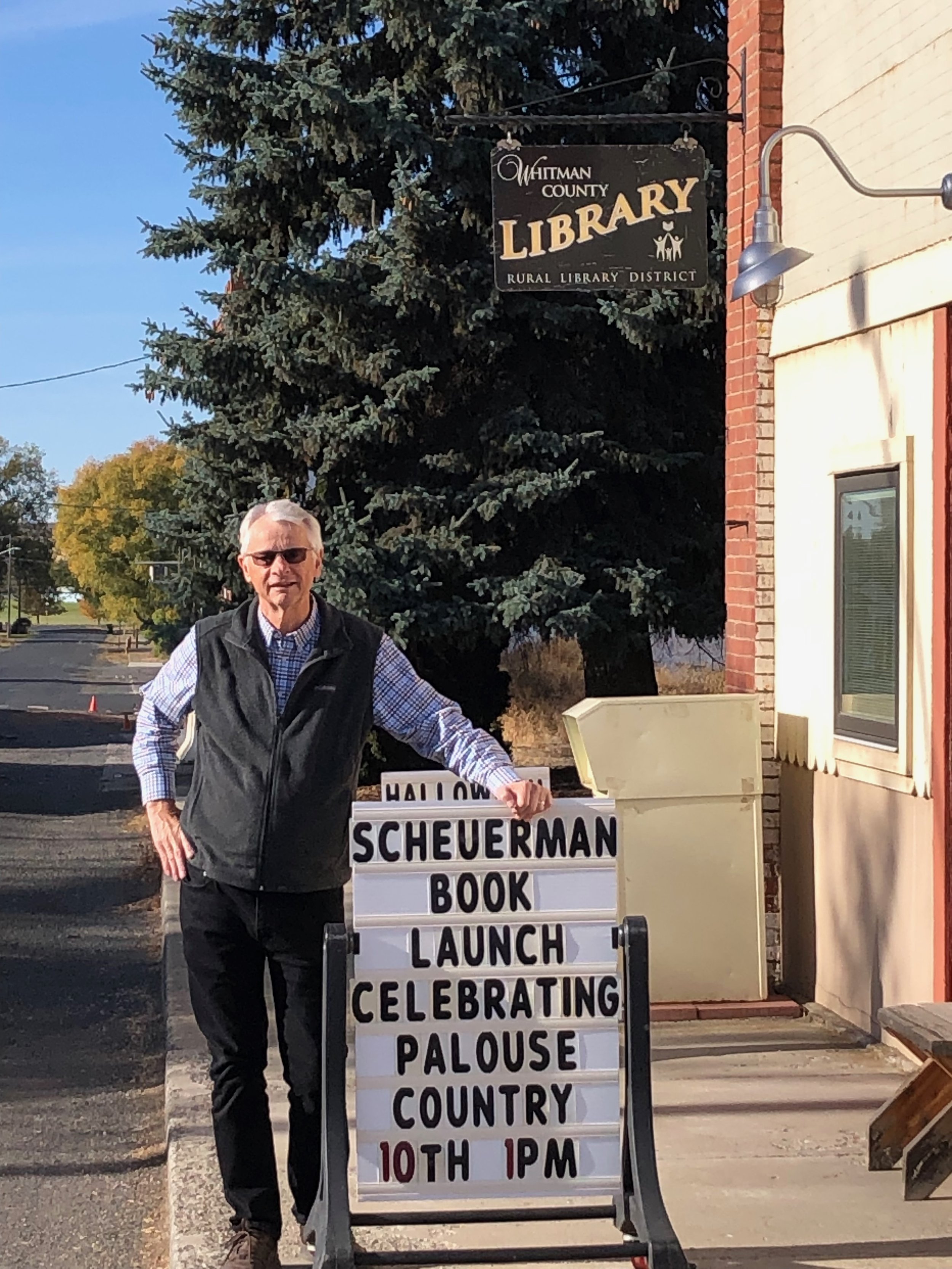

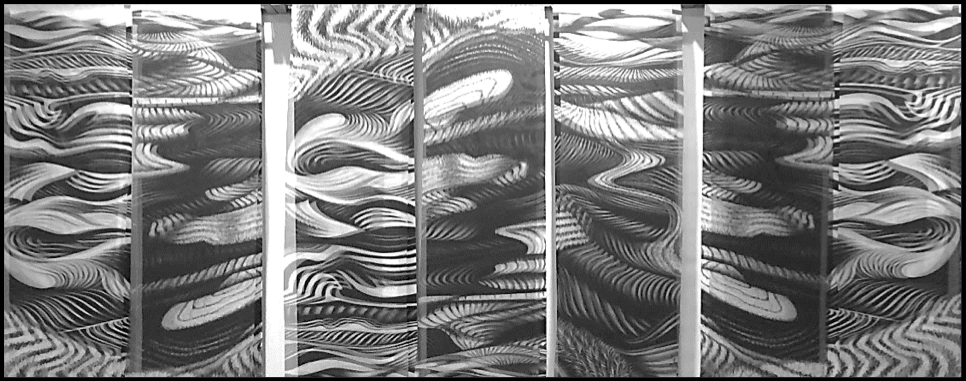

The stark, mysterious black-and-white photography of Kirby’s Wheatcountry (2001) shows unpeopled agrarian vistas from Texas to Washington. Essayist Richard Manning writes of the contrast between the imaginative West of the national consciousness—reshaped since settlement and largely uninhabited, and landscapes tended by farmers who contend with the vagaries of weather and maneuver through an array of government programs to provision the masses. Kirby’s monochromatic views bear the titles of nearby locations scarcely known or seen by outsiders, but that conjure memory and meaning to locals. His Palouse series includes Diamond and Lancaster (places where farmers came from miles around to procure seed wheat), Harrington and Pomeroy (home to area flour mills), and the Snake River port of Central Ferry, which remains one of the Northwest’s largest grain exporting terminals.

Having grown up in the vicinity, I immediately recognized Kirby’s “Wheatfield III, Repp Road, Endicott, Washington,” which shows a prodigious stand of ripening wheat cloaking an enormous swirl of sloping summer-fallow beneath a stack of cumulus clouds. The Repp family had the only pool for miles around before the town built one in the 1960s, so kindly taught a generation of us how to swim. The matriarch of the clan is still active at age 104 and her nephew Mike Lowry—our state’s twentieth governor who contributed to normalized US-Russia relations in the 1990s, surely helped harvest that very hill. Trends in the depopulation of the countryside are found throughout the nation, even as affordability of houses in small towns has helped keep some populated with newcomers to sustain local schools, churches, and clubs. Shrinking numbers of farmers remain as vital carriers of intimate knowledge about the land and growing conditions, and of practical skills that keep bringing forth the crops.

Themes of change upon the landscape mixed with agrarian wonder characterized many poems by Pulitzer Prize winning author Howard Nemerov (1920-1991). Although the New York native spent much of his life in academia, he traveled widely through the New England countryside and with publication of his 1955 collection The Salt Garden, Nemerov’s refined, contemplative verse took on more practical tones in defense of the land. Poems like “Midsummer’s Day” and “The Winter Lightning” reflect upon the timelessness of the seasons and consider a consilience with humanity’s ephemeral presence. In “A Harvest Home” an abandoned vehicle stands in a recently harvested field (“So hot and mute the human will / As though the angry wheel stood still / That hub and spoke and iron rim”), while marvelous creatures of the wing appear throughout the day—jays “proclaim” dawn, afternoon crows “arise and shake their heavy wings,” and an owl “complains in darkness.”