Stories and paintings that relate a range of interpretations regarding contemporary and future existence add voice and visibility to diverse perspectives on land use. Consolidation of family farms in recent decades into larger corporate enterprises and the commodification of grain—William Cronon’s “transmutation of one of humanity’s oldest foods,” warrant high regard for stewardship of the land. Reinvigoration of Americans’ deep-seeded social memory and cultural capacity can guide landowners and public officials who contend with environmental challenges and finite production acreage. When Conrad Blumenschein told me in the 1970s about leaving Russia for America just before the outbreak of World War I, ten families lived on a dozen farms of about 320 acres each scattered along the road between my hometown of Endicott and the Palouse River some seven miles to the north. (The other two landowners lived in town.) Numbering some fifty people, most attended one of two Lutheran churches in the area—the Missouri Synod in the country, and the Ohio in town, and two country schools enrolled the area’s children through the eighth grade. Many of these families were related to each other, and regularly gathered for summer harvest labors, fall butchering bees, and various ceremonies and celebrations.

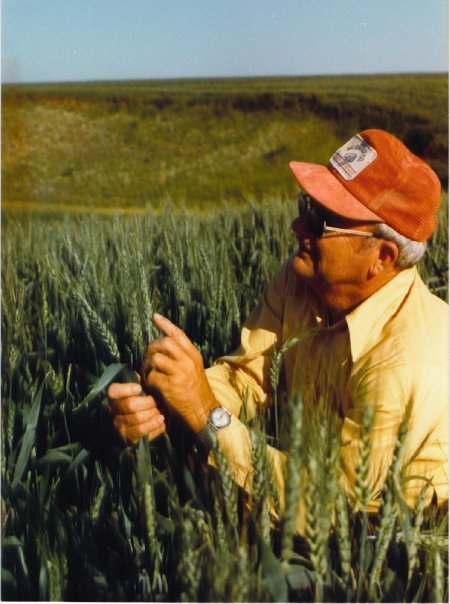

A half-century later when I began interviewing first generation immigrant elders like Conrad Blumenschein and Mary Morasch, the number of farms had fallen to nine with some consolidation of property holdings among the seven families of thirty-two individuals who remained. The size of area farms had increased to an average of 550 acres, and both country schools had consolidated with the larger town district that offered instruction through grade twelve. My father was able to complete our month-long harvest on about that much acreage by keeping in good repair the old tractor and pull-combine that had teamed up for at least a quarter-century to make the annual run. Based on a photograph from the time, family member Rob Smith captured the scene in the watercolor A 3L-160 Harvest, c. 1970 (2012, named for the equipment model numbers). The price of a bushel of wheat rarely rose to $2 from 1960 to 1973, when a controversial U. S. trade deal to supply the Soviet Union with grain boosted prices to as much as $6.25. The long-sought optimism felt by growers ushered in a year of equipment upgrades and land purchases encouraged by Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz’s 1973 “get big or get out” slogan. Favorable Russian harvests the following year coupled with reduced federal subsidies contributed to America’s 1970s “farm crisis” followed by years of rural economic stagnation.

The year of Butz’s remarks was coincident with publication of British-German environmental economist E. F. Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as If People Mattered (1973). The contrast in perspectives regarding the wellbeing of farmers could not have been starker. Schumacher (1911-1977) considered federal promotion of larger production acreages and related needs for more expensive equipment to be a reckless hubris of domination. Inspired by thinkers like Tolstoy and Gandhi, Schumacher understood the forces of modernity to be complex but fueled by a blinkered preoccupation with short-term solutions that ignore ancient ways of sustainable living. He invoked a sovereignty of reason to advocate for enterprising farmers who valued the longstanding natural and social commons that provided economic benefits well worth protecting. Without such public policies vast numbers of younger farmer families would be driven from the countryside. And so they have been. (Ohio farmer-essayist Gene Logsdon, author of The Mother of All Arts: Agrarianism and the Creative Impulse [2007], responded to Butz’s admonition with advice on how to, “Get small and stay in.”)

Palouse Harvesttime Smoky Sunset and Pine City Grain Elevator Firestorm Aftermath (2020)

Columbia Heritage Photographs

In the fifty years that has now passed since my 1960s high school FFA speech on world hunger, global population has increased by four billion and the world has consumed some 1.3 trillion barrels of oil. (Approximately one and a half trillion metric tons of carbon dioxide have been released into the atmosphere since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.) The result has been a warming of the earth’s surface by 0.6 degrees C. and the disappearance of a million square miles of spring snowpack in the northern hemisphere. The pace of change has led to devastating impacts on biodiversity and prospect of neo-Malthusian food security crises. Regional trends can only be discerned over time but already some disturbing patterns are evident. Since 2020 annual precipitation has declined across the Columbia Plateau and in the summer of that year the only firestorm in living memory made national headlines when it devastated the Palouse hamlets of Malden of Pine City and destroyed vast areas of standing grain. Notable modern writers like James Rebanks, author of Pastoral Song: A Writer’s Journey (2021), reflect upon the impact of climate change upon agriculture and natural systems in passionate and informed prose as compelling as Rachel Carson. The urgent planetary imperative is to live within the biosphere’s means through new economies and methods of sustainable production.

My boyhood rural neighborhood of several thousand acres that had been home to about fifty souls in 1900 is comprised today of just eight farms. All but one are parts of larger family-owned operations whose members also own or lease other cropland in the area. (The average Palouse Country farm size in 2020 was approximately 1200 acres.) Only four households are located on the same seven-mile stretch that supported those ten families a century ago, and today are populated by just five adults whose grown children live elsewhere. In between these habitations one can now see lonely clusters of dying locust trees, broken fences, and the rusted equipment of abandoned farmsteads. The trend has brought debilitating effects on rural communities that contend with closures of local stores, banks, and public service by reaffirming pioneer values of hard work, integrity, and teamwork.

The broader demographic impacts on rural life and labor are consistent with trends over the past two centuries that have changed the nature and necessity of worker communities. In 1840s pre-industrial America, for example, a farmer could produce an acre of hand-broadcasted wheat yielding about twenty bushels from approximately fifty hours of annual work using simple implements like a single-shear plow and scythe. (Soil exhaustion and other factors in early nineteenth-century France and Germany contributed to average yields of less than half that amount, or about ten bushels per acre; yields on unmanured fields in England were in the range of fifteen. Continental Europeans commonly faced substantial crop failure and famine at least once every ten years.) A single day’s harvest by an able-bodied reaper could cover up to one acre. By 1900 an American farmer equipped with horse-pulled gang plow, harrow, and mechanical drill still produced about twenty bushels from an acre but in some ten hours. An experienced crew operating a reaper-binder and steam-powered thresher at that time could cut about forty-five acres a day for some 1,200 bushels (31 tons) of grain. A farmer in 1940 using a gas-powered tractor, three-bottom plow, and combine with 12-foot header further reduced annual per acre labor to 3.5 hours.

Harvests Yesterday and Today—Different Times, Identical Location

Lautenschlager & Poffenroth (1911) and Klaveano Brothers Threshing Outfits (2019)

Four miles north of Endicott, Washington

Dryland grain yields increased three-fold nationally during the twentieth century and Palouse Country yields of eighty bushels per acre are common today along with diesel-powered, satellite-guided equipment that make crop rows of linear perfection. High-capacity combines now cost as much as a million dollars and feature sidehill leveling, cruise control, and electronic monitoring of threshing functions that automatically adjust to crop load. Modern farmers invest scarcely fifty minutes in total annual per-acre labor, and can harvest three hundred acres in a ten-hour day with a combine header forty feet wide to yield some 30,000 bushels (900 tons) of wheat, or 72,000 bushels of corn. Sickles endure. Modern versions feature four-inch-wide chromed, serrated triangular sections arranged toothlike in a row that runs the length of the header and moves back and forth at lightning speed. Such mechanical marvels represent the output of a thousand reapers and twice as many binders laboring in harvest fields before the Industrial Revolution. (Substantial numbers of others were tasked with carting unthreshed stalks to barns, flailing grain, tending livestock, and other related tasks.) A phalanx of these modern behemoths cruising through a field of golden grain evokes appreciation for techno-mechanical ingenuity, and still stirs ancient feelings of gratitude for agrarian bounty. Dayton watercolorist Paul Strohbehn’s dramatic Sorghum Hollow Gold (2018) shows three immense John Deere Titan combines rising from a Palouse hillside chaff cloud.

Among the most recent developments in farm mechanization is the application of autonomous driving capabilities to tractors and combines. Technology has also transformed bulk grain handling facilities at strategically located places like Endicott and other locations along railroads and river ports. Endicott was platted in 1882 by the Oregon Improvement Company, a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific Railroad, on its Columbia & Palouse branch line. This route tapped the fertile grain district along a route from the main NPRR transcontinental line at Palouse Junction (present Connell, Washington) eastward to Endicott, Colfax, and eventually Pullman and Moscow. An extensive network of feeder lines later fanned across the northern and southern Palouse to other farming communities.

Columbia & Palouse Railroad Grain Storage Flathouses, Endicott, Washington (c. 1910)

Northwest Grain Growers High-Capacity Unit Train Loading Facility, Endicott (2022)

With the recent merger of the local Endicott-St. John grain storage cooperative with Walla Walla and other groups to form Northwest Grain Growers, the new entity constructed a storage and 110-car unit train loading facility in Endicott since the line there had been constructed with heavier rail weight capacity. The project called for construction of seven immense steel silos located to bring total capacity there to approximately 3,100,000 bushels. The new facility, which became operational in 2020, is designed for rapid one-day loading of the trains which are capable of holding 100 tons of grain per car for a total capacity of 420,000 bushels. Grain is trucked from farms and other elevators for rail shipment and barging along the lower Columbia River to Portland and Kalama for distribution worldwide.