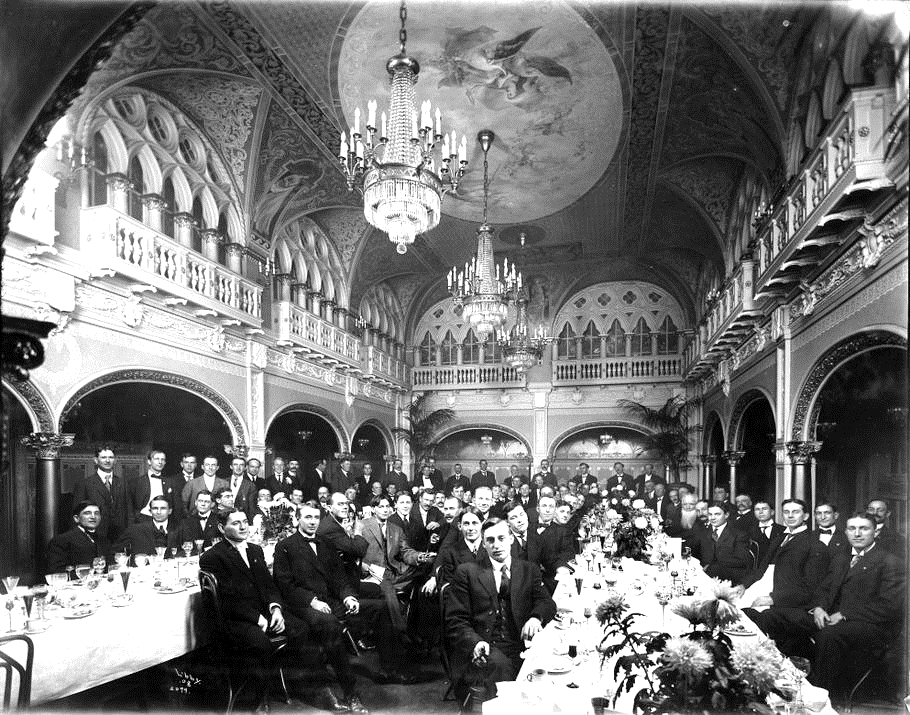

“Feeding the New Global Middle Class” Illustration, The Atlantic

I read with special interest the article “How Will We Feed the New Global Middle Class” by Charles C. Mann in last month’s issue of The Atlantic (March 2018). It not only addressed this pressing question in terms amply supplied with meaningful examples and disturbing statistics, but referenced the important research long undertaken by a longtime friend and supporter of our work at Palouse Colony Farm, WSU plant scientist Dr. Stephen Jones. Mann’s article casts the controversy about supplying a growing world population’s food supply as a century-long contest between the “Wizards” and the “Prophets.” He characterizes the former as advocates of commodity production and scientific innovation exemplified by Norman Borlaug, father of the “Green Revolution,” and the “Prophets,” or proponents of natural ecosystem conservation like William Vogt. I commend the entire article for your review of this complex question, but thought Mann’s discussion of Stephen Jones’s research on perennial wheat to represent a rare convergence of Wizard-Prophet interests.

Perennial grains do not exist in nature so cereal crops must be planted year after year which necessitates field tillage and attendant labor and other inputs. Development of a crop like the Salish Blue wheat hybridized by Jones and his agronomist colleague Steve Lyon offers hope for a grain of sufficient milling quality that can produce from the same plant for two to three years. Jones and Lyon have told me that the pioneers of perennial grain research were a team of Russians headed by Nikolai Vavilov (1887-1943), a brilliant scientist who paid for his independent thinking by perishing in one of Stalin’s GULAG prisons. Vavilov formulated the “Centers of Origin” theory (a phrase first used by Darwin) for the geographic origins of the world’s cereal grains. Vavilov had been a protégé of Robert Regel, Russia’s preeminent pre-revolutionary era botanist. Regel had appointed the brilliant young Saratov University scientist head of all Russia’s agricultural experiment stations on the very day the Bolshevik Revolution broke out in 1917. Vavilov became a prime-mover in the organization of the first All-Russian Conference of Plant Breeders in Saratov in 1920.

The group’s June 4 opening session marked a milestone for world science as Vavilov delivered his famous paper, “The Law of Homologous Series in Hereditary Variation,” in which he put forth the first hypothesis on plant mutation. For subsequent related research that led to the formulation of a law on the periodicity of heritable characteristics, Vavilov came to be known as the Mendeleyev of biology. Although Vavilov’s enthusiastic grasp of problem definition in crop breeding proved easier than problem solving, upon Regal’s death later in 1920 he was named director of the Agricultural Ministry’s Department of Applied Botany and Plant Breeding, and went on to organize the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Nikolai Vavilov (c. 1930), Library of Congress

Vavilov derived many of his insights from extensive travels “across the whole of Scripture” in Transjordan (Israel) and Palestine. He traveled widely in the Middle East and pored over religious texts in order “to reconstruct a picture of agriculture in biblical times.” His ideas were significantly influenced by the field studies of German botanist Frederich Körnicke (1828-1908), curator of the Imperial Botanical Gardens in St. Petersburg in the 1850s, and Aaron Aaronsohn, Director of the Agricultural Experiment Station at Haifa, Palestine. In an article published in 1889 on the history of world grains, Körnicke had identified a specimen of wild emmer found in the collection of the National Museum of Vienna as the progenitor of all modern wheats. He urged botanists to conduct expeditions in the foothills of Mt. Hermon where it had been found in order to better document its origin and range.

Aaronsohn subsequently recorded his historic 1906 discovery of the grain: “When I began to extend my search to the cultivated lands [near Rosh Pinna], along the edges of roads and in the crevices of rocks, I found a few stools of the wild Triticum. Later I came across it in great abundance, and the most astonishing thing about it was the large number of forms it displayed.” Indefatigable Vavilov followed Aaronsohn’s itinerary to locate this relict stands of the famed “Mother of Grains” and found it growing nearly forty inches tall with stiff, six-inch long beards. His further research demonstrated that emmer’s ancestral range extended throughout northern Transjordan and into Turkey.

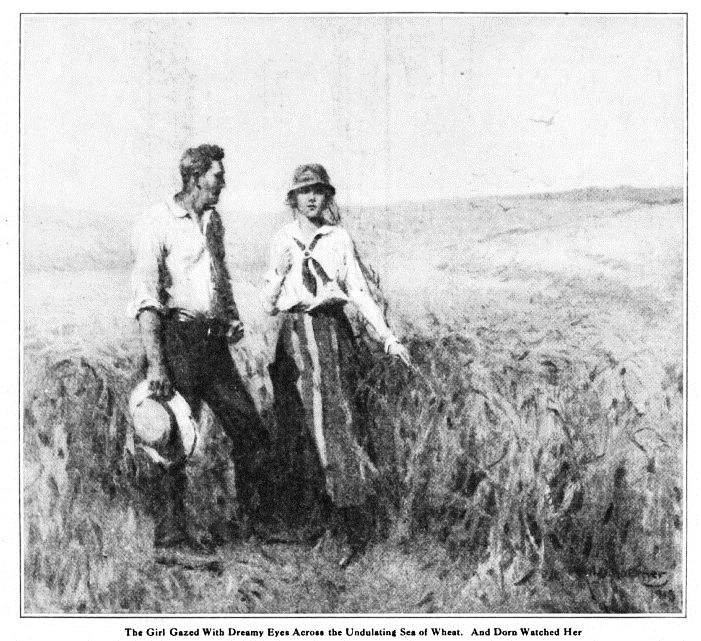

Vavilov met Washington State College agronomist Edwin Gaines and his celebrated botanist wife, Xerpha, at the 1932 Sixth International Genetics Congress at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. This celebrated gathering was attended by some 550 of the world’s leading geneticists. The conclave’s highlight was the much-anticipated delivery of Valvilov’s presentation on geographic distribution of wild cultivar relatives. His paper focused on the importance of preserving threatened landraces and their progenitors for future breeding stock and pure research. He further postulated the origin of modern hard red wheats in the Fertile Crescent (“southwestern Asia”) and soft whites in northwestern Africa. Vavilov also described ancient selection methods by which early agriculturalists unconsciously conducted spontaneous variety selections.

In spite of myriad challenges in hosting such a prestigious event in the midst of the Great Depression, the Gaineses invited Vavilov to Pullman while on his extended trip to several western states. Vavilov accepted the offer and spent several weeks in the late summer and fall of 1932 touring grain research stations in the Northwest clad in ever present tie and fedora. The time of year and fecund Columbia Plateau laden with grains spawned from his homeland may well have reminded Vavilov of lines from the celebrated Russian poet Pushkin extolling life on the steppe. He could quote verse at length in fluent English. The Gypsies imagines new life in fall-sown wheat even as hunters and their dogs trample fields underfoot. The image poignantly anticipates Vavilov’s own fate a decade later as a victim of Stalin’s purges: “…the winter wheat will suffer from their wild fun” while the stream ever “passes by the mill.”