This blog is a continuation of a series on my (Richard's) trip across the country visiting important sites related to heritage and landrace grain studies. View the other posts in the series here.

Hillwood Estate Museum, Ann McClellan, Interpreter

We’re big breakfast cereal lovers at the Scheuerman household! I still enjoy a good bowl of Post Grape Nuts or Toasties Corn Flakes, though I wish they would cut down on the sugar. I had some vague memory of the Post family’s association with Post cereals. C. W. Post was a man of humble origins and a passion for healthy living who built the Postum Cereal Company into a substantial empire. After he passed away in 1914, his only child and heir, Marjorie Meriwether Post, took over the family enterprise and transformed it into the General Foods Corporation and a host of other related concerns. In the 1930s Marjorie lived in Moscow as the wife of the U. S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Joseph Davies. She became fascinated by Slavic culture and began collecting treasures from Russia’s Imperial Age as many tsarist objects and works of art were sold at auction by the Soviet government in order to obtain hard currency. Ms. Post had special interest in Catherine the Great and was among the few who could afford the finest pieces which began the vast collection at her Hillwood estate west of Washington, D. C. She arranged to have the mansion and its treasures donated to the nation upon her death in the 1970s.

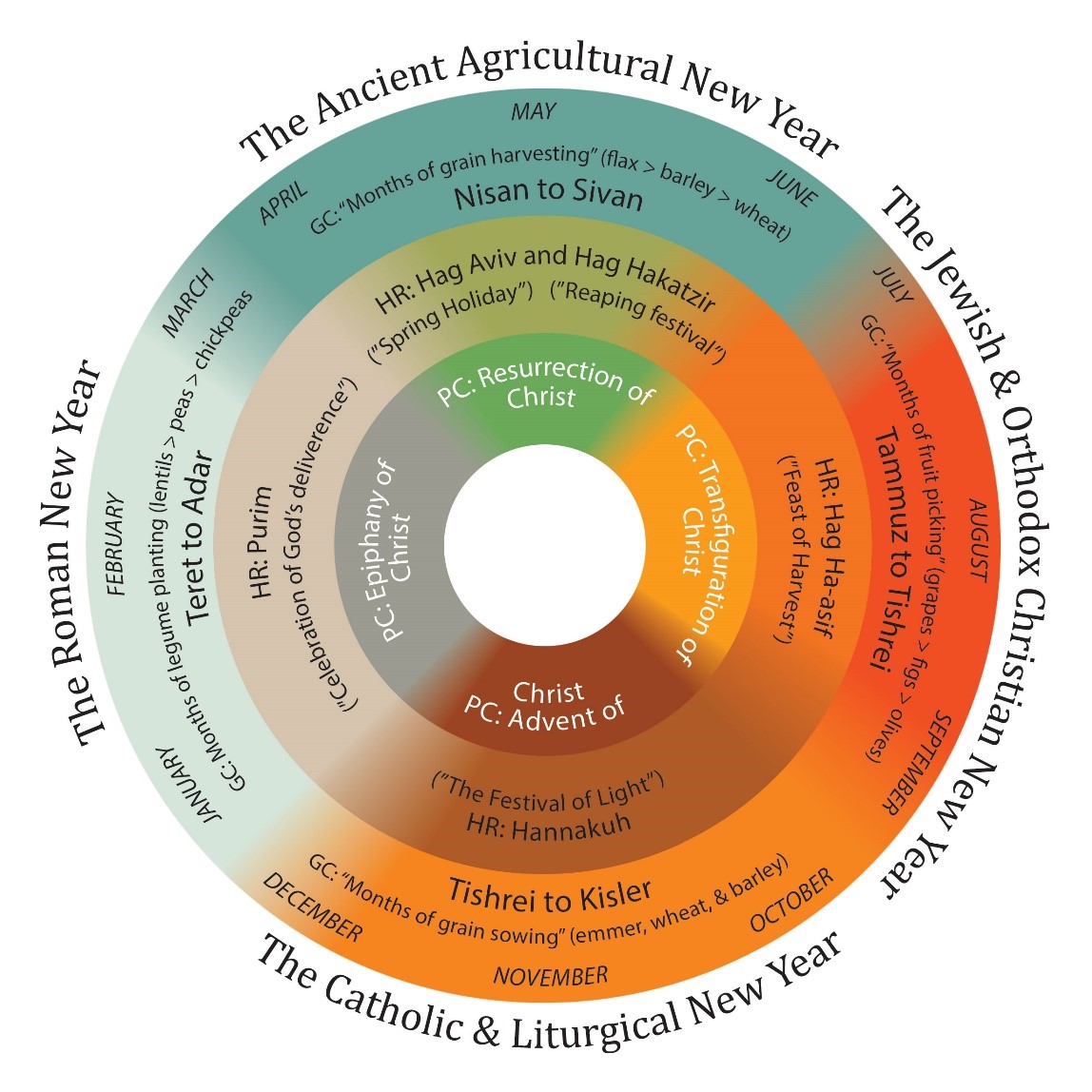

Russian Empress Catherine the Great (1729-1796) commissioned a breathtaking project to transform a vast area near the summer palace at Tsarskoe Selo (Pavlovsk), the “Tsar’s Village” west of St. Petersburg, into an allegorical landscape shaped by her conception of this Russian rural idyll. She found in Orthodox priest and agronomist Andrei Samborsky (1732-1815) a teacher with the proper background to tutor her grandsons and a small circle of privileged classmates like Prince Alexander Golitsyn. After graduating from the Kiev Academy in 1765, Samborsky had studied agriculture in England and served as chaplain at the Russian Embassy in London, married an Englishwoman, and returned to Russia to begin tutoring the Russian dukes in religion and natural science in 1782.

Buch Chalice with Gold Wheat Stem; presented by Catherine the Great to Nevsky Cathedral, 1791

Hillwood’s Imperial Palace Service and Furnishings from Pushkin, Russia

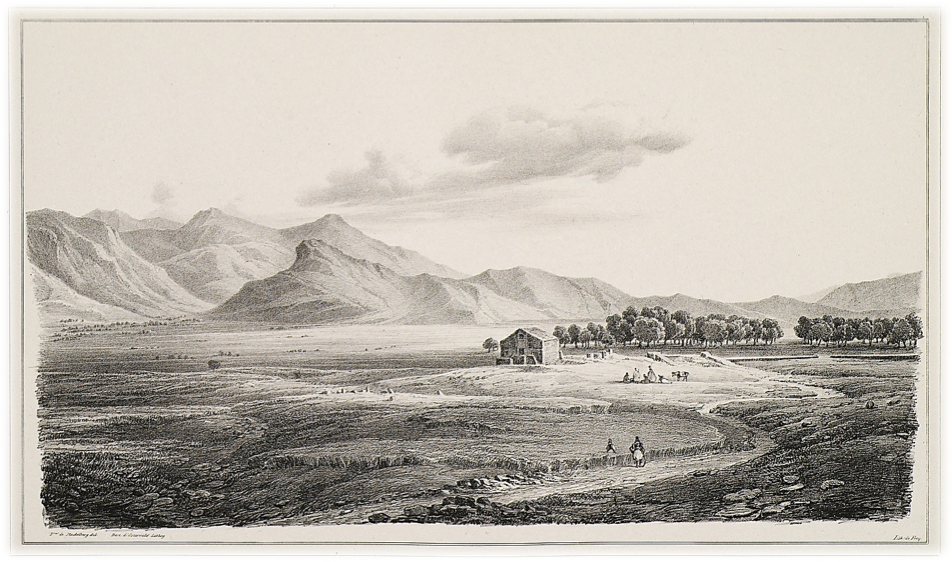

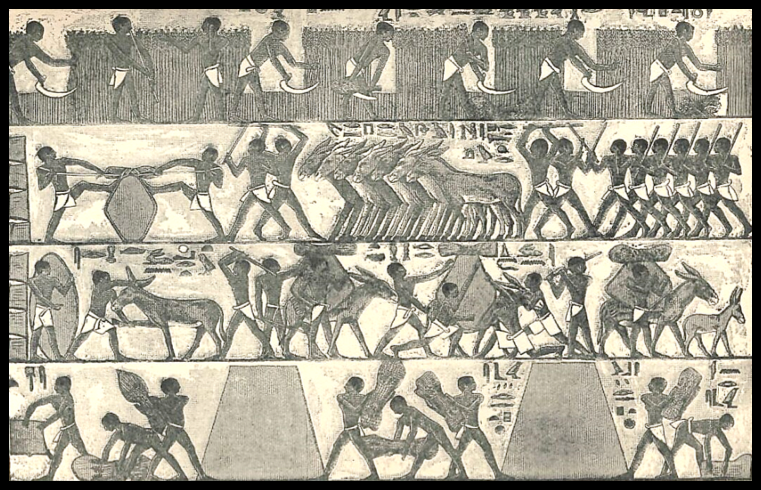

With the Empress’s support, Samborsky formulated plans for an Imperial Farm and School of Practical Agriculture on a thousand acres adjacent to Tsarskoe Selo which became an important state institution devoted to the improvement of crop and livestock production and farm management. An engraving from the time shows Samborsky plowing with an improved English implement as his distinguished Order of St. Vladimir medal hangs from a nearby tree. Open land in the vicinity was sown to wheat, rye, pasture grass, and other crops while workers labored nearby in the 1780s on Pavlovsk, the splendid summer palace of Catherine’s son, Paul I, and from 1792 to 1796 on his son’s Neoclassical residence, the Alexander Palace. The first structure built at Pavlovsk was the open air Temple to Ceres (later Catherine’s Concert Hall, 1780) by the empress’s favored architect Charles Cameron (1745-1812), a colonnaded Doric rotunda that originally contained a statue of Catherine as Ceres and painted panel An Offering to Ceres.

The Imperial Farm originally constructed from 1828 to 1830 featured buildings of Tudor Gothic country style designed by Scottish architect Adam Menelaws (c. 1750-1831) with a single story Cottage Palace built nearby as an izba containing rooms for visiting members of the imperial family. Outbuildings included a stone barn, stables, granary, and dairy, and a kitchen redesigned in 1841 to serve as a Grand Ducal School. The cottage was expanded to three floors in 1859 with the addition of bedrooms, and dining and drawing rooms to become the ocher-colored Farm Palace which Alexander II (1818-1881) used as the family’s preferred summer residence for the rest his life. When time permitted, Alexander especially enjoyed his Blue Study which displayed favored paintings of rural scenes and fine bindings, and where he signed the Emancipation of the Serfs decree in 1861.

Mt. Vernon National Historic Site

“I hope, some day or another, we shall become a storehouse and granary for the world.” --George Washington, letter to Marquis de Lafayette, June 19, 1788

“The great Business of the Continent is Agriculture.” --Benjamin Franklin, “The Internal State of America,” c. 1790

“I am never satiated with rambling through the fields and farms, examining culture and cultivators, with a degree of curiosity which makes some take me to be a fool, and others to be much wiser than I am.” --Thomas Jefferson to Marquis de Lafayette, April 11, 1787

I had day of splendid Virginia sunshine for the short drive from Washington, D. C., down to Washington’s Mt. Vernon estate overlooking the Potomac River where I made arrangements to visit the park’s living history farm and the nation’s most recently presidential library—the spectacular Smith Library for the Study of George Washington. Prior to leading freedom’s cause in the Revolutionary War, Washington first leased Mt. Vernon after the death of his half-brother, Lawrence, in 1754, and obtained full title in 1761 upon his sister-in-law’s death. Washington significantly expanded his holdings to 8,000 acres through acquisitions of Mansion Farm, Ferry Farm, Dogue Run Farm, Muddy Hole Farm, and River Farm. He began experimenting with various kinds of crop varieties in the late 1780s in order to move from tobacco to grain production in order to eliminate reliance on slave labor and in to improve the land’s fertility. My very helpful host was Lisa Pregent, who manages Mt. Vernon’s Living History Farm, where our Palouse Heritage Scots Bere barley will once again be growing after an absence of over two hundred years!

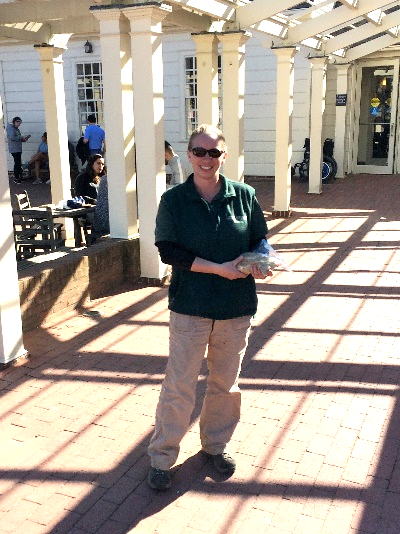

Mt. Vernon National Historic Site and Living History Farm, Lisa Pregent, Farm Manager, holding Palouse Heritage Scots Bere Barley Seed

; and George Washington’s Restored Octagonal Threshing Barn

I continued down the winding road about five miles through the sparsely populated countryside to the recently rebuilt George Washington Gristmill and Distillery. (Someday soon they’d also like to reconstruct his farmhouse.) I arrived right at 5 PM closing time and the place was about empty, so thought my chances of any kind of guided tour were slim. But I was pleased when Head Miller Cory Welshans emerged along the lane leading to the mill with an inviting smile that seemed to say, “I’ll spare time for anybody with information about George Washington’s original grain culture.” And indeed he did show me around the grounds and invited me to return on my trip back from Williamsburg to meet Historic Trades Manager Sam Murphy.

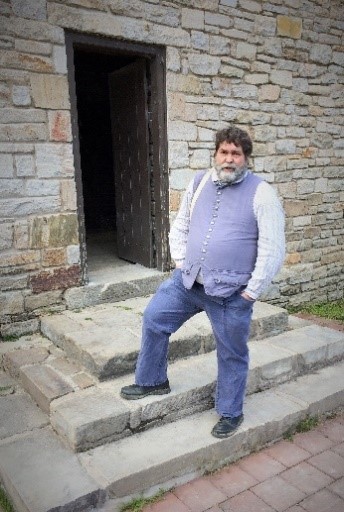

Cory Welshans, Head Miller

Sam Murphy, Historic Trades Manager

In no tribute to my time management skills, I did return but this time a few minutes after closing hours though Sam and the milling team could not have been more accommodating to my interests. I got a grand tour of all three stories of the operating mill and found Sam, like Cory, to be a storehouse of knowledge and very interested the old White Virginia May wheat for milling and Scots Bere barley for both milling and brewing.

Mt. Vernon National Historic Site Gristmill and Distillery

Sam provided some valued insights into Washington’s agricultural know-how and business savvy:

"President Washington did many things as a political and military leader, but here we really emphasize George Washington the agricultural entrepreneur. He led the transition from tobacco to grain culture in this region and built the two-story octagonal threshing barn based on a European design that reduced his loss to soil and sky by traditional methods from 20% to less than 10%. He also experimented with new grains from Europe and Asia, and installed the first Oliver Evans stone milling and silk-sifting equipment in the country. The reconstruction here is the only one of its kind presently operating.

"Washington developed a very lucrative milling business by vertically integrating his operations. He raised high quality milling grains for that time and installed sophisticated silk-sieve sifting equipment to separate the flour into three products—superfine white flour for the best bread and pastry flour, middlings with the bran and endosperm, and “ship stuff” for making hardtack or sea biscuit. He traded considerable grain to Caribbean markets for rum which he sold here in the Colonies, and also used those profits to import goods from China. So he was into global trade and vertical business integration long before those terms became fashionable."

Thanks again, Lisa, Corey, and Sam, and I can’t wait to see these Early American grains once again flourishing where they did in the time of our Founding Farmers!

Williamsburg, Virginia

I continued to the southeast on my rental car expedition for some 170 miles via Richmond to Colonial Williamsburg, America’s famed and meticulously restored 18th century community with generous support from the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. family. I was invited to meet with Ed Schultz and Wayne Randolf who have managed Great Hopes Plantation there and who have been wanting to restore the period’s authentic grain culture to the farm. I found them to be very gracious hosts and incredibly knowledgeable regarding Early American agricultural history. Various Williamsburg museums and libraries also contained works relevant to my “Hallowed Harvests” study.

Great Hopes Plantation Rye Field, Ed Schultz, Journeyman Farmer

William Prentis Store Field

What’s more, I hadn’t dined at the King’s Arms Tavern since first visiting Williamsburg with my wife, Lois, our parents, and my sister Debbie in the 1970s. I was pleased to find the same colonial era wines, savory pot pies, and desserts on the menu that we found back then. Today, however, some craft ales said to be based on old recipes had been added to the mix.

King’s Arms Tavern Marquis, Colonial Williamsburg

But I really knew I was where I was supposed to be after checking in late at night to the Quarterpath Inn and finding a framed print of this work by the French artist Jean Millet that I had been writing about in “Hallowed Harvests” hanging above my bed. Below it are some lines I composed about its significance.

Jean Millet, Harvesters Resting (1854)

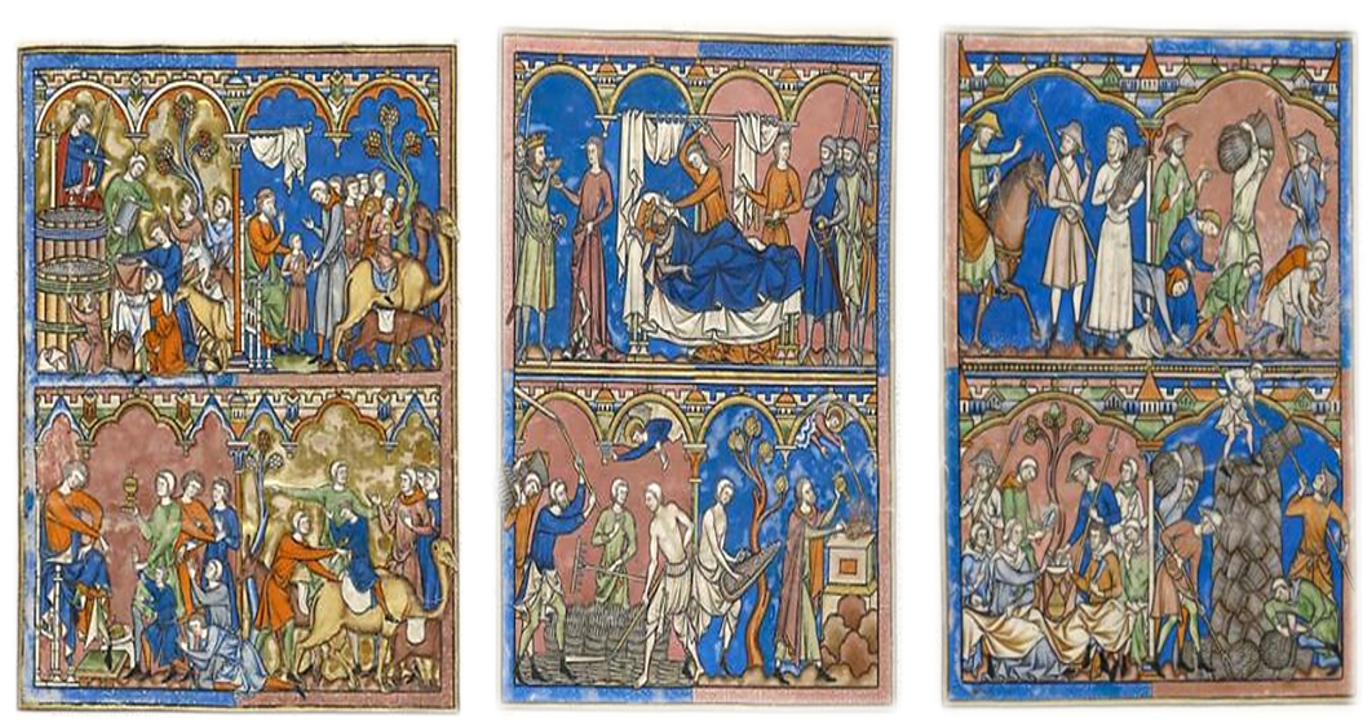

Millet sought to paint “pictures that mattered” and the work he considered his masterpiece, Harvesters Resting—Ruth and Boaz (1857), earned the artist his first medal and is among very few paintings he explicitly based on a biblical theme. The canvas bathes Millet’s aesthetic mission in a spiritually charged golden pink light that merges appreciation of nature with faith, while the complex composition reflects associations with precedents like Breughel’s The Harvesters. In this monumental idyll, Millet reinterprets biblical Ruth and Boaz with contemporary relevance in clothing and setting to illustrate the mutual respect born of her courage and his benevolence. A jarring disparity is expressed between rustic peasant piety and privation.

Painting from a carefully moderated palette of soft tones, Millet clothes Ruth in blue, the symbolic color of purity typically seen in Renaissance portrayals of Mary, the mother of Jesus. The artist almost certainly intended this in accordance with Boaz’s proclamation that Ruth be known as a woman of excellence. Boaz presents her to his laborers, most of whom recline and eat their fill from a communal dish while Ruth clings to her grain as if she were protecting a child. She is vulnerable, excluded, and poor—like those who exist on the margins of society in any age. Yet a man of means shows uncommon compassion and chooses her to be a member of his household and offers promise of a new life.

The pithy sayings and light-hearted verse that made Benjamin Franklin’s Almanack a best-seller in Colonial and Early America reflects his creed regarding liberty of persons as a “key freedom” so Americans could own property and enjoy the fruits of their labor in the philosophic tradition of John Locke and John Milton. But in Franklin’s views, such freedom should have reasonable limits since unrestrained personal liberty could transform into licentiousness that threatened the public good through radically unequal distribution of wealth. While touring Scotland and Ireland in 1771, diplomat Franklin had seen firsthand the widespread abject poverty of the countryside which he attributed to absentee landlords and exploitive farming practices. Franklin proposed an amendment to the Pennsylvania constitution of 1776 to limit the large concentrations of farmland and other property which he believed would be “destructive to the Common Happiness of Mankind.”

Keep Within the Compass Print (Carrington & Bowles, 1784)

Agrarian toil was likewise associated with moral wellbeing in Early America. The popular Keep the Compass allegorical broadsides, printed in England with separate versions for young men and women, depicted the benefits of proper behavior and hard work. Colorful scenes around a draftsman’s compass show the perils of vice beyond the instrument, while a harvest scene and church steeple inside represent keys to success symbolized by a sack of treasure. “KEEP WITHIN COMPASS AND YOU SHALL BE SURE,” the poster admonishes, “TO AVOID MANY TROUBLES OTHERS ENDURE.“

Stay tuned for the next installment of this blog series on Richard's "Great American Heritage Grains Adventure."

Richard's trip has been made possible by generous support from The Carolina Gold Foundation, Anson Mills and Glenn Roberts, Seattle Pacific University, the University of California-Riverside Department of History, and Palouse Heritage.