The Palouse Heritage Blog

Daily Bread, Liberty, and the Orphans of Ukraine

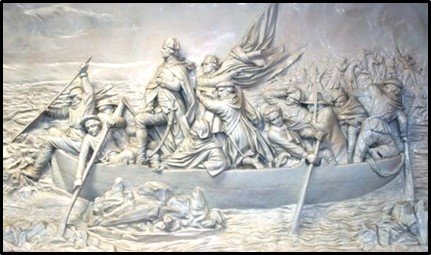

Goodness, Grain, and Humankind— Thoughts Concerning Ukraine and Our Nation’s Founders

Thanksgiving Traditions—A Heritage of Gratitude Part Two

Thanksgiving Traditions—A Heritage of Gratitude Part One

Ethos Stone Mill and Barnard Griffin Winery Partner with Palouse Heritage for Tasting

Amber Eden Grain and a Memorable Harvest

Whole Grain Health—at Home and Abroad

The Grand Grain Refrain—1935 Harvest Reminiscences in Verse

Amber Waves of Eden Grain

Of Grains and Gluten

Climate Change — Back in the Day

Plenty is Revealed, Beautiful Upon the Earth

Scythes, Sickles, and Mr. Tusser

The “Cerealization” of Europe

A Medieval Bread Buffet in the Tri-Cities!

The Farm Novel