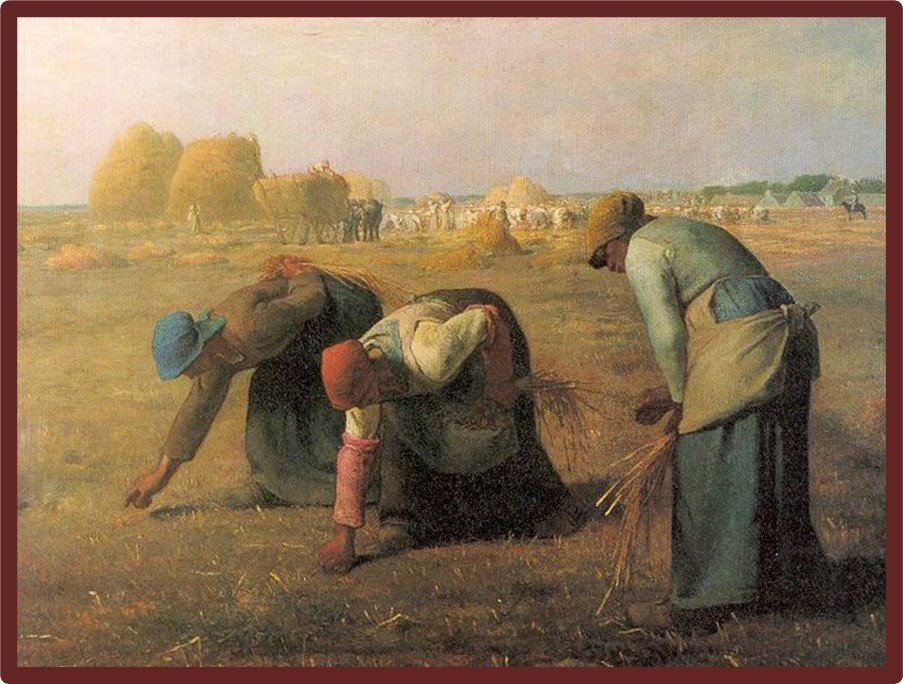

Ohio farmer and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Bromfield deeply loved farming as cooperative art in the classical sense of working in partnership with nature. He combined experience from a rural upbringing with agricultural studies at Cornell and in journalism at Columbia to author nineteen novels and eight books of non-fiction. Bromfield established Malabar Farm in 1939 on a thousand acres near his native Lucas, Ohio, to promote soil conservation, animal husbandry, and sustainable “permanent” farming. Bromfield explained his agricultural principles in a book named for the farm which had become an enormously popular tourist attraction and is now a state park and living history farm. Malabar Farm (1948), illustrated with woodcuts including scenes of wheat, oat, and corn harvest by Kate Lord, is based on Bromfield’s 1944 journal “written when the weather was bad and the work was light.” The book relates dinner table conversation and musings on a range of wartime economic issues, talk about Gertrude Stein and Edith Wharton, “farmer religion,” and political constraint on human tendencies to exploit and do harm.

In 1940 writer-conservationist Russell Lord (1895-1964) and Bromfield founded the Society for the Friends of the Land, a non-profit advocacy organization to publish the quarterly journal The Land (1940-1954) and promote sustainable agriculture. Honorary members included venerable environmentalist prophet Liberty Hyde Bailey, Soil Conservation Service founding director Hugh Bennett, Aldo Leopold, and other leading figures. The group envisioned an interdisciplinary forum as relevant to agrarian affairs as Atlantic Monthly was to urban interests by offering an enriching humus of pragmatic and cultural perspectives. Edited and illustrated by the Lords from their farm near Bel Air, Maryland, The Land was published in Columbus, Ohio, for fifty-two issues under Bromfield’s oversight and featured short stories, articles on farming, science, politics, religion, and poetry. It became an influential voice for a permaculture based on “interdependent” biodiversity and multinational cooperation. The approach contrasted with developments in a world of nationalist rhetoric growing out of rising East-West tensions and the advent of controversial new technologies. Bromfield expressed the group’s hopes for the movement with allusion to emerging issues of the time in a membership appeal:

Friends of the Land attempts to create an awareness in the minds of all our citizens of the importance to them of the wise use of our soil and water, and to provide a forum for all points and shades of opinion on conservation, to the end that the people themselves shall form their own opinions and take proper action. …There is a great revolution going on in American agriculture. This is being brought about by economic and population pressures, including increasingly high taxes, mounting labor costs and mechanization. These pressures make it imperative that the farmer who is to survive must adopt new and more efficient methods for the production of food, feed and fiber. …Friends of the Land would have our people see that forests, cover crops, grassland farming, inter-row cropping, stream flow, water power, transportation, commerce, and flood prevention are all tied together to promote our prosperity and to determine our standards of living and therefore our health and happiness.

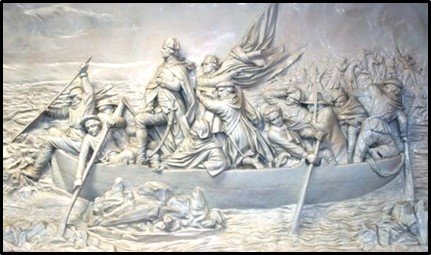

Bromfield’s words underscore the holistic nature of the founding Friends perspectives against the backdrop of events that profoundly affected American farming. They reveal the emerging fault lines between a new order of global cooperation and sustainability envisioned under Franklin Roosevelt, Henry Wallace, and Gifford Pinchot in contrast to unilateral approaches pursued under the Truman administration to increase production at home and unilaterally advance American foreign policy objectives. Despite misgivings over Wallace’s progressive advocacy, his concern over the militarization of science, and conciliatory attitude toward the Soviets, Truman retained him as a cabinet member for six months until Wallace delivered a speech in September 1945 advocating conciliation with the USSR. The new president had given Stalin the benefit of the doubt but Soviet hegemony in Eastern Europe and the specter of totalitarianism led to a fundamental shift in his thinking by 1947 and the beginning of the Cold War.

Truman’s pick for Secretary of Agriculture, Clinton Anderson (1895-1975), reorganized America’s post-World War II agricultural economy to increase domestic food production, alleviate global post-war shortages, and enter the foreign policy realm to counter communist tendencies in developing nations. New Deal initiatives in soil conservation, rural electrification, and other realms celebrated by WPA artists and authors gave way to government contracts with industry scientists, university researchers, and corporate laboratories. Discussion of the contest over the future wellbeing of the planet played out on the pages of The Land throughout the 1940s and early ‘50s. Bromfield and Lord contributed numerous articles as did other notable figures in conservation including Wallace Stegner, Paul Sears, and William Vogt. A collection of popular selections illustrated with Kate Lord’s woodcuts appeared in 1950 as Forever the Land: A Country Chronicle and Anthology.

While soliciting a range of viewpoints on domestic and world affairs, plant genetics, global population growth, and other topics of agrarian relevance, Lord and Bromfield expressed concerns over “quick buck” policies they feared would transform fields into factories and enlist technologies that risked unintended environmental consequences. During the war years, the USDA had suspended publication of the annual Yearbooks but released a 900-page compendium titled Science in Farming—The Yearbook of Agriculture, 1943-1947. In the new volume’s introduction, Secretary Anderson dismissed fears about DDT, genetic testing, and “[concern] that life be too abundant.” A generally favorable review of the book by The Land’s assistant editor James R. Simmons included some skepticism: “I decline to eat the bread that is no longer bread but a puffed-up something that has about as much flavor as ground peanut shells…. I can’t understand why it is necessary to grind the nourishment out of our grain and ship something that must be ‘enriched’ with chemicals before it is fit to nourish the human body.” Simmons also touched on recent national changes that were detrimental to rural vitality—interstate highways that bypassed smaller communities, centralized processing and marketing facilities, and a growing societal affluence that prized consumerism above conservation. The Land’s summer 1953 issue featured “The World Gets Warmer” by meteorologist Harry Wexler, one of the first widely published articles on the likelihood of climate change due to burning of fossil fuels. Bromfield wrote passionately about the dangers of militarism and the nuclear arms race other Land contributors warned of potential dangers from atmospheric testing of atomic bombs.