The Palouse Heritage Blog

A 2022 Harvesttime Collage of Sights, Sounds, Smells & Tastes

Of Hackles and Scutching— Old World Flax for New World Linen

Living History “Open-Air Museum” Farms, Self-Discovery Accokeek, and Beyond

Van Gogh’s Landscapes—Agrarian Beauty and Life’s Renewal

“Modern US Wheat Has Roots in Ukraine” - My Interview With NPR's The World

Daily Bread, Liberty, and the Orphans of Ukraine

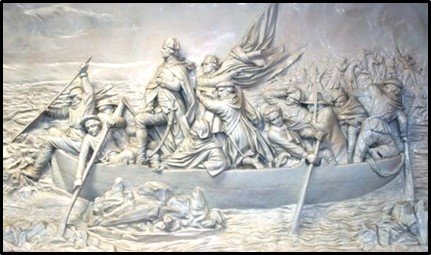

Goodness, Grain, and Humankind— Thoughts Concerning Ukraine and Our Nation’s Founders

Thanksgiving Traditions—A Heritage of Gratitude Part Two

Thanksgiving Traditions—A Heritage of Gratitude Part One

Ethos Stone Mill and Barnard Griffin Winery Partner with Palouse Heritage for Tasting

Amber Eden Grain and a Memorable Harvest

Whole Grain Health—at Home and Abroad

The Grand Grain Refrain—1935 Harvest Reminiscences in Verse

Amber Waves of Eden Grain

Of Grains and Gluten

Climate Change — Back in the Day

Plenty is Revealed, Beautiful Upon the Earth

Scythes, Sickles, and Mr. Tusser

The “Cerealization” of Europe