Although few references to gleaning are found in early medieval farm records or literature, the practice was known to parishioners through sermons and readings from biblical texts like Ruth. Agrarian by-laws after the thirteenth century that regulated peasant manorial obligations provide scant evidence that gleaning in the traditional sense was widely practiced. Virtually all able-bodied villagers worked in harvest and received a share of the crop for meagre although sufficient sustenance, and hordes of migratory workers seasonally roamed throughout Europe to meet area labor shortages during the critical weeks of summer. Until the advent of mechanical reapers and threshers in the nineteenth century, the cutting and binding of sheaves could not be done without some loss of the stalks, and more grain fell by the wayside when the sheaves were set into shocks to facilitate drying and gathering onto wagons. Although barley and oats lacked the level of gluten that made wheat the preferred grain for baking, they still offered the poor important sources of nutrition as flatbreads, soups, and other foods. Oats tended to shatter more easily than wheat when ripened and barley stalks could be more brittle, so both crops may have been gleaned to some extent to supplement villagers’ diets.

Johann Schönsperger, Scything and Reaping (1490)

Johann Schönsperger, Teutscher Kalendar (Munich, 1922)

Since landlords sought to turn out their livestock to forage on harvested stubble fields cleared of shocks, gleaners generally had only a week or two to complete their labor. Landowners zealously guarded the harvest from sheaf-stealers, not an uncommon crime at the time, which led to by-laws specifying limits and qualifications for gleaning in the traditional sense. English royal manor instructions of 1282 permit only those incapable of earning any income to glean: “The young, the old, and those who are decrepit and unable to work….” William Blackstone’s Commentary later explains, “By the common law and custom of England the poor are allowed to enter and glean upon another’s ground after the harvest without being guilty of trespass.”

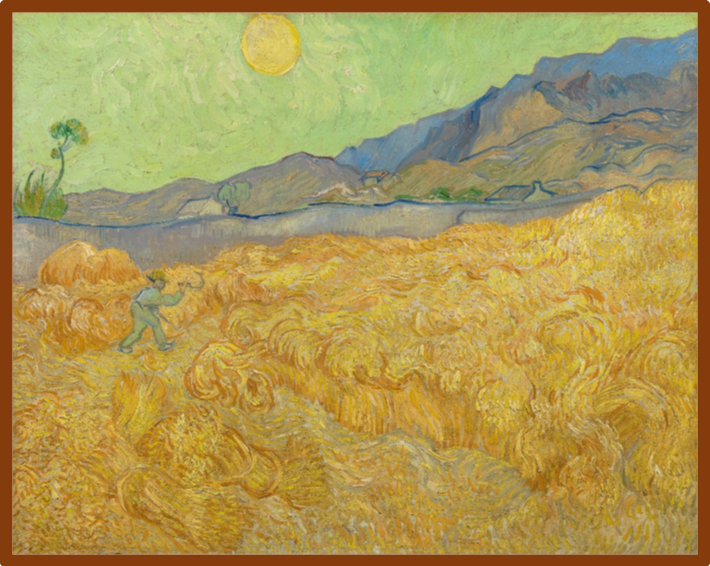

Well into the present era throughout much of Europe, great bands of contract laborers, including both men and women, were led by the overseer who organized teams of workers as if a military operation. Mowers were usually teens (“lads”) and men who wielded sickles, broadhooks, or long-handled scythes and carried whetstones to keep them razor-sharp throughout the day. (The Proto-Indo-European root of the terms “scythe” and “sickle” is sek, also cognate to schism and sex, means to divide, or cut.) The men were followed by gavellers, often wives of the mowers or younger women, who raked the stalks into rows (gavels) for tying into substantial sheaves, or which were left unbound in rows to be thrown with wooden forks by pitchers into horse-drawn wagons. These were driven by carters to large barns and piled and piled by stackers into enormous heaps to await wintertime threshing by flail or horse “treading.”